Photo 1: The speakers at the Outlook for Tech R&D Cooperation with Countries under the New Southbound Policy conference pose for a photograph; Source: Conor Stuart,

The government of Taiwan launched a policy aimed at increasing trade and investment links with the 10 ASEAN countries in Southeast Asia as well as six South Asian Countries, Australia and New Zealand in September of 2016. The “New Southbound Policy” is a ramped up version of previous southbound initiatives. As we have previously reported, former iterations of the policy under the presidencies of Lee Teng-hui and Chen Shui-bian were primarily aimed at finding cheap manufacturing bases with a cheap supply of labor for Taiwanese businesses, whereas under the leadership of president Tsai Ing-wen, the new policy has widened the scope of the policy in terms of target countries and shifted to a focus on integrating industry innovation and forming an Innovative Growth Partnership.

Although Taiwan is aiming to diversify its trade through the policy, it has a lot of competition in the region, including from China’s One Belt One Road initiatives, which cover many of the same countries, as well large-scale investments from South Korea, Japan and free trade agreements with the countries and regions targeted by the policy. A free trade agreement between Hong Kong and ASEAN is expected to be completed by the end of the year, according to press reports.

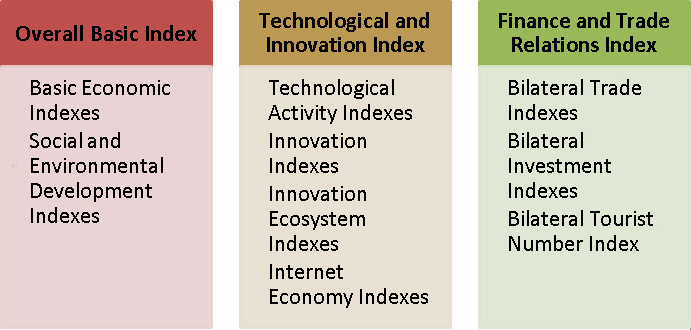

In light of this competition, the Taiwanese government has established a database, which traces various variables concerning the target countries from the year 2000 to the present and are updated each month. These are grouped into overall basic indexes, including basic economic indexes and social and environmental indexes, technological innovation indexes and finance and trade relations indexes.

Lien Wen-jung, a research fellow with the Chuang-hua Institute of Economic Research, gave a rundown of the information being collected on each country at a recent conference in Taipei, titled “Outlook for Tech R&D Cooperation with Countries under the New Southbound Policy” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The main indexes by which countries are categorized in the database, as presented by Lien Wen-jung.

Lien also revealed some of the initial findings that the database has contributed to. He stated that Malaysia’s three big technological and innovation indexes all ranked higher than five other New Southbound Policy countries (Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and India), especially in terms of access to venture capital funds.

Among the “ASEAN 5” countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand), individual virtual social media use is quite high, suggesting potential for social media-based business model development. However, businesses in the ASEAN 5 and businesses in Taiwan are neck and neck in terms of progress in this sector, and ASEAN businesses have an advantage in understanding Southeast Asian customer preferences, said Lien.

He added that the potential for businesses to innovate is lower in the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, but they are advancing fast, while the advantage of Taiwanese businesses is slowly ebbing. Due to improvements in the innovation environment, like improved intellectual property right protection (although their ranking is still lower than Malaysia, Indonesia and India), companies are spending more on R&D there, boosting innovation.

With the exception of Malaysia, the influence of ICT on service-based industries such as medicine, education and finance, is low and technology and equipment used in these regulated industries are tied to government acquisitions and support. Lien suggested that, on this basis, Taiwanese companies that want to unroll ICT-based technological applications in these countries should target those countries in which government acquisitions of advanced technology are rated more highly, such as Indonesia and Vietnam. Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines are rated the highest among the ASEAN 4 in terms of application of the latest technology, but all fell short of their 2012 index, whereas Vietnam has made significant progress in this category, with its ranking rising from 3.6 in 2012 to 4.1 in 2016.

Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam’s “Industry-academia cooperation level” ratings are all relatively low, the reason for which is the relatively low caliber of the research institutes and R&D output by companies, along with the lower levels in mathematics and science education quality and deployment of scientists and engineers, according to the data Lien provided. This suggests that industry academia cooperation would be challenging there.

The initiative has variously been described as a “benevolent Trojan horse” and as providing aid for mutual development. Lien cited Chen Sin-horng stating, “To distinguish oneself in certain fields, Taiwanese parties must innovate together with important local influencers (including government, business leaders, and innovators). We need to substantially address demand in Southeast Asia to solve problems or provide services, in order to form a new international innovation chain and ecosystem.”

Lien stated that the policy would borrow from the experience of Japan’s “trade + investment + official development assistance + local regional integration” four-pronged strategy.

Lien also pointed to some factors which might prove to be obstacles to the policy, including the lack of diplomatic relations, in that China has continued to interfere in Taiwan’s foreign relations and that the countries have other choices, besides Taiwan. Another factor he listed was the limit to the resources of the Taiwan government, which makes it difficult to compete with Japan and China. The final obstacle he listed was the limited ability for the government to mobilize business owners. Conversely, there are several factors that may work in Taiwan’s favor, such as Taiwan’s participation in global organizations, the network of ethnic Chinese living in many of the target countries and Taiwanese citizens with familial ties to Southeast Asia as well as Southeast Asian students who study in Taiwan, and the development policies of many of the governments of the target countries, which focuses on the digital economy, innovation and entrepreneurship, government services and disaster prediction.

Lien cited various strategies by rivals within the reason, including South Korea, which he says takes a top-down approach, providing target governments with a tech R&D framework through organizations like the Korean Advanced Insititute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and the Science and Technology Policy Institute (STEPI). This is then aimed at strengthening the country’s science and technology skills by bringing talent to South Korea for training, then areas for development are set in a combination of meeting local needs and emphasis on industries in which South Korea is adept. Japan has adopted a bottom-up approach which first identifies local needs, strengthens skills in the field in question in the country as well as in Japan and then hopes that this can influence government policy.

China also has the China-ASEAN Technology Partnership Program, which incorporates seven stages as listed below:

1. Policy Consulting:

Supporting Chinese dedicated entities to engage in joint-research with related entities in ASEAN focused on national technology development plans and technology policy. Providing support for Chinese technology management experts in providing ASEAN countries with innovation policy consulting services.

2. Technology Services:

Supporting Chinese businesses, research institutes, scientists and engineers in travelling to ASEAN to provide technology consulting and other services.

3. Human Resources Development

Establishing a China-ASEAN applied technology training center to train technology management personnel in ASEAN. Helping ASEAN technology workers to travel to China to engage in training or cooperative research.

4. Cooperative Research

Supporting businesses, research institutes and universities from China and ASEAN in working together on core technology R&D and commercialization, as well as working together to develop research in local languages and jointly establishing national and regional standards.

5. Building joint laboratories

Providing support to Chinese businesses, research institutes and universities to work with partners in ASEAN to jointly establish laboratories or joint research centers in particular fields, as well as building professional public technology platforms and long term stable personnel exchange and cooperation mechanisms.

6. Jointly Establish Technology Parks and Pilot Scheme Bases

Supporting Chinese businesses and technology parks in cooperating with ASEAN partners to establish technology parks. Through establishing pilot bases, it is hoped that China’s advanced applied technologies can be taken up in ASEAN countries and popularized.

7. Technology Transfer

Establishing “China-ASEAN technology transfer centers”, to build a service platform that enables common use of data and resources, to help businesses and technology parks from both China and ASEAN cooperate. Organizing China-ASEAN technology forums to create a discussion platform for business cooperation.

The director of the Vietnamese Economic and Cultural Office in Taipei Mr. Tran Duy Hai was also present at the conference and although he stated that cooperation across a lot of fields is already occurring, from administrative departments to economic and technological cooperation, protectionism in certain areas may serve as an obstacle to furthering trade relations, particularly in the agricultural sector – with agricultural import restrictions, he stated.

The database has yet to be made accessible to the public.

|

|

| Author: |

Conor Stuart |

| Current Post: |

Senior Editor, IP Observer |

| Education: |

MA Taiwanese Literature, National Taiwan University

BA Chinese and Spanish, Leeds University, UK |

| Experience: |

Translator/Editor, Want China Times

Editor, Erenlai Magazine |

|

|

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|