There was a lot of buzz around patent monetization at the 9th 2016 Cross-strait Patent Conference, which was held from December 6-7 in Taipei. Much of this buzz comes because China has managed to forge ahead with patent monetization schemes, such as loans using patents as collateral and patent enforcement and infringement insurance, while Taiwan has been largely unable to follow suit, much to the ire of patent professionals on the island. This has a lot to do with the financial regulations in Taiwan and the lack of incentive for banks to take on such loans or establish mechanisms for this kind of insurance. Conversely, as Beijing has adopted patent monetization as policy and offers subsidies for these kinds of loans, some IP professionals have questioned how effective the model will prove without these incentives, which are really supposed to serve as simply an initial catalyst, rather than play a long-term role in this model. For its part, patent monetization in Taiwan has largely centered on patent transactions, patent pools and patent enforcement, much of this undertaken by non-practicing entities (NPEs), which have often been referred to as patent trolls. Many of these NPEs deal primarily with US patents held by Taiwanese companies as their main focus, and patent monetization in Taiwan itself has seen little progress.

Patent Monetization:

On the second day of the conference, the same question kept cropping up again and again from Taiwanese audience members as well as the general director of the Technology Transfer and Law Center of Taiwan’s Industrial Technology Research Institute, Wang Peng-yu, “How did you incentivize your banks to agree to offer loans with patents as collateral?” Although the Chinese representatives went some way to giving a satisfactory answer to this question, it is clear that the government’s control over banks in China plays a big role and that the Chinese government is willing to spend a lot on this policy, including taking up a large chunk of the risk of the loans by serving as a guarantor for the loan, as Jili Chung pointed out in our last issue.

Monetization in Taiwan

Figure 1: Joseph Chang speaking at a previous event in Taipei; Source: Conor Stuart

Joseph Chang, the CEO of Faith Intellectual Assets, was one of the only Taiwanese representatives at the conference who deals extensively with patent monetization in the private sector. His firm is a recent spin out of the Taiwan-based unit of Transpacific IP. He said that throughout his career he has always been interested in how patents can be monetized and pointed to early efforts by companies like Intellectual Ventures to promote the idea of “patents as products” and of “patent monetization”, which peaked around 2008. In the US market this led to a surge in the “enforcement” of patent rights, which spurred in the America Invents Act (AIA) in 2013, aimed at cracking down on patent infringement suits by non-practicing entities (NPEs). He stated that AIA has led to a polarized “M-shaped” market for patent enforcement and patent grants in the US and led to a shortage of funding for research and development in Silicon Valley, due to a loss of confidence in the value of patent rights.

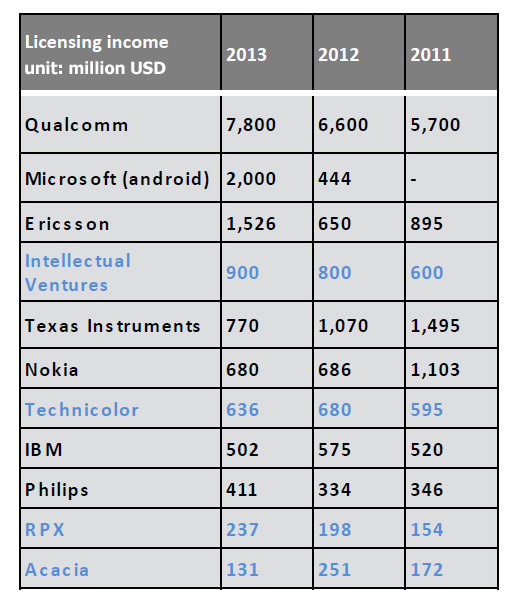

Chang describes his company as a firm which engages in patent transactions, these transactions include the transfer or licensing of patent rights, cross-licensing agreements and infringement settlements. He eschews the word “patent troll” in reference to NPEs, pointing to what he perceives as unfairness in the use of this term, applied as it is only to independent entities who enforce their patent portfolios, but not to the licensing departments within practicing firms which are essentially engaged in the exact same practice with similar patents. To illustrate this he showed the licensing revenues of non-practicing and practicing entities from 2011-2013 in the table below (see Figure 4).

Figure 2: Non-practicing entities marked in blue; Source: Joseph Chang's presentation

For practicing entities, licensing revenue makes up a substantial proportion of total revenue. Chang estimated that patent licensing revenue accounted for a third of Qualcomm’s total profit, while for companies such as Microsoft or IBM, which rely on traditional patent licensing, it can range from 1% to 2% of total revenue. He stated that the reason Qualcomm can derive so much revenue from its patents, is that the firm spends a substantial amount of money, possibly more than the amount it spends on applying for patents, on patent monetization.

Chang says that he’s always hopeful for increases in transactions, as he sees this as equivalent to patent “liquidity”, which helps reinforce the concept of patent rights as property. He runs his business on the basis of demands from buyers, some of which are motivated by profit, while others have more strategic motives behind their demand. When calculating the royalties for licensing agreements, he suggested keeping in mind the litigation and royalty stacking. He stated, however, that after the AIA was introduced, patents in the US are more vulnerable to invalidity proceedings, which he suggested poses a threat to the liquidity of the patent market.

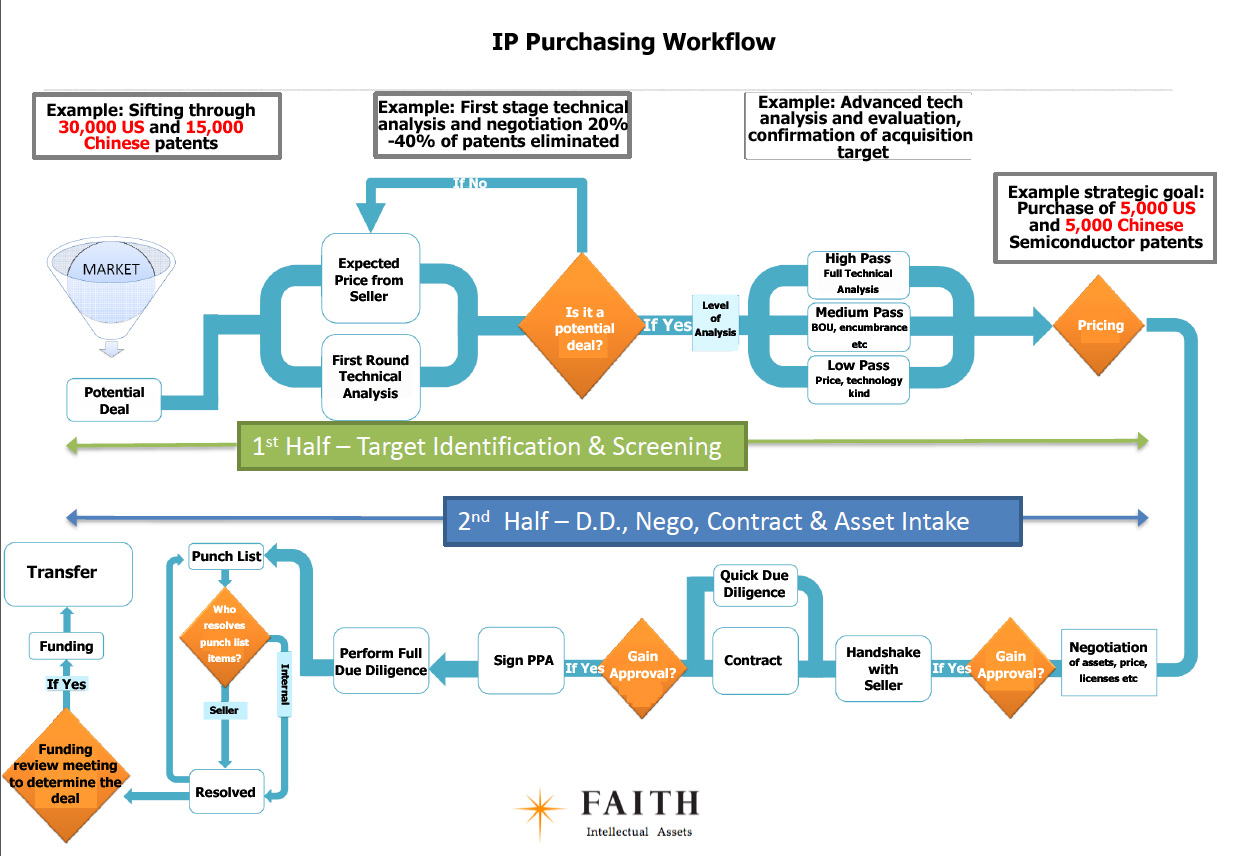

Chang says that over the years his work has shifted from maximizing intellectual property asset value to accelerating the speed with which intellectual property assets are monetized. If you want the maximum value, you really have to focus on litigation, he said, not simply conduct transactions, which is his focus. Chang gave an example workflow of negotiating the purchase of patents, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 4: IP Purchasing Workflow; Source: Joseph Chang's presentation

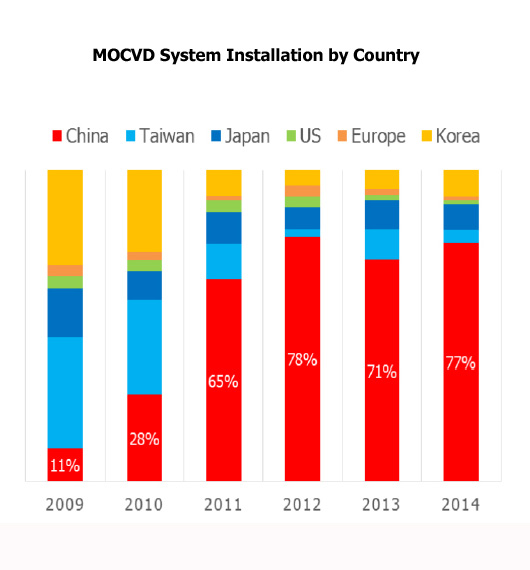

Chang said he was impressed by China’s rapid development in the IP field, pointing to the growth in China’s share of the MOCVD market from 2009 to 2014 as an example (see Figure 2).

Figure 3: MOCVD market share; Source: Joseph Chang's presentation

In terms of the rest of Northeast Asia, Chang stated that South Korea has attempted to follow the US model over the last 15 years, which has allowed it to catch up to Japan, which founded the IP Bridge in 2013, in an attempt to modernize its outdated modes of thinking about patent rights.

What differentiates China from Japan, South Korea and Taiwan in its huge domestic market and the relative lack of reliance on the US market that results from this, Chang said. US patents don’t have as big an impact on the Chinese market, but this does not mean that China has stopped working on its international patent strategy.

Wang Peng-yu stated that patent professionals in Taiwan are keen to get to a point where they can get more out of patents than what litigation can offer. This necessitates conceptualizing a concrete value for a patent, even if this value has not yet been fully realized at the point of valuation, he added.

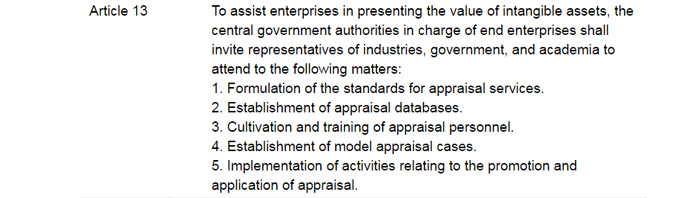

Wang stated that Taiwan has not been idle over the past years in terms of working towards the goals of patent monetization and offering loans using patents as collateral. He urged the Taiwanese delegates present to address lawmakers on the issue of easing financial regulations concerning intangible assets, in the hope that a legal framework can be established. He cited Article 13 of the Statute for Industrial Innovation as a springboard for this:

Figure 5: Article 13 of the Statute for Industrial Innovation; Source: MOJ

There are still many obstacles in place, however, he added, including a failure to establish a patent appraisal database and financial regulatory restrictions.

Patent Monetization in China

Figure 6: Hu Junjian; Photo by Tommy Tang

Hu Junjian, head of the Second Division of the Patent Affairs Administration Department at SIPO, gave an almost exhaustive list of models for patent monetization, including patent licensing, patent assignment, raising finance using patent rights, using patented technologies in industry, converting patent rights into shares, forming patent pools and applying for patents to become standard essential patents (SEPs). He stated that to realize this goal SIPO had had to implement four measures:

- Platform: the formation of the “Intellectual Property Right Monetization Public Service Platform” to ensure effective monetization of patents and conformance to regulation.

- Professional Organizations: the setting up of organizations to facilitate patent monetization and to train professionals in the specific work needed for this, such as valuation, fund management and consulting.

- Capital: encouraging core industries to invest in patent monetization and patent pools.

- Industry: raising awareness of intellectual property policy among companies.

He went on to say, “Our ultimate objective is for patents to be incorporated into an asset exchange platform, equivalent to that used for shares, bonds and staple goods”.

Figure 7: Wang Shuanglong; Photo by Tommy Tang

Wang Shuanglong, head of the Department of Market Management of the patent section at SIPO, stated that of the many experimental schemes that SIPO has launched involving patents, patent financing and patent insurance have developed the quickest. These schemes are largely aimed at small and medium-sized businesses, as larger businesses, such as mobile phone giants Huawei and ZTE, don’t need to use their patent rights as collateral to access finance, he said, adding that these kinds of loans are really an attempt to break through the bottleneck SMEs face in raising capital.

Wang stated that the two most important aspects of patent monetization are the business model used and the valuation. The reason SIPO started to move in this direction, he said, was the realization that innovative SMEs which were able to get support in terms of intellectual property were able to maintain steadier growth. SIPO was then eager to see how else they could use IP as a tool for development, which led them to the possibility of financing using patents as collateral.

Wang drew attention to one of the major problems of patent valuation citing the example of a medium-sized company which has secured finance from a bank using patent rights as collateral. If the company is unable to pay back the loan, the bank is then assigned the patent rights and will attempt to sell them off to recoup the loan. Wang stated that this violates accounting principles, and explains why the market in the US, Japan and Europe have been unable to adopt the “patent as product” model. This is essentially the problem of subjectivity in valuation. One man might think he’s selling a chicken, for example, while the potential purchaser thinks he’s buying a goose, said Wang. If you view patents, purely as a product, a small business could be vulnerable to giving up potentially valuable assets to fundraise. So there needs to be a clear understanding of to whom the intellectual property belongs. Wang then stated that he doesn’t think that the sale or assignment of patents is a good idea, advocating instead for temporary rental of the rights, as putting a value on a patent for a one time transaction is difficult and subjective. Agreements on taking royalties for a certain period of time are more practical.

Wang referred to four government measures that have been rolled out at the local level to help facilitate these kinds of transactions:

- Government as guarantor: the government participates in the establishment of credit guarantee corporations or works with credit guarantee corporations to set up a guarantee fund. The guarantee corporation provides a guarantee for the loan extended to SMEs with patent rights as collateral.

- Risk compensation: financial risk prevention funds are established. When SMEs are temporarily unable to make loan payments, the payments will be temporarily put up by the risk prevention fund until the sum can be repaid by the SME.

- Subsidies for cost: a certain amount is provided to the guarantee corporation in subsidies; subsidies are provided to companies to cover the cost of patent valuation.

- Regulatory easing: credit and loan staff at the Banking Regulatory Commission have been freed from meeting certain targets, which incentivized banks to offer patent-based loans.

Wang also stated that each player in the scheme has their own motivation for taking part in the scheme, from industry, which is able to use the scheme to raise funds, to the financial organizations, that can meet new clients through the scheme, offering them services from other areas of their business and the government which is able to support industrial development.

Wang pointed to five models for patent financing, as below:

- Direct Financing Model (Bank + Patent Rights as Collateral)

A loan is granted with only the patent rights as collateral (no tangible assets): A patent holder can use valid patent rights as collateral for a loan and be given financing from a commercial bank based on the valuation of the patent and then repay the principal with interest at regular intervals.

- Indirect Financing Model (Bank + Patent Rights as Collateral + Guarantee)

The patent holder offers the patent rights as collateral to the guarantee corporation, the guarantee corporation offers a guarantee to the bank, and then the bank and the patent holder sign a loan agreement.

- Combination Financing

Combination with equity shares (bank + patent rights as collateral + equity shares as collateral)

Combination with tangible assets (bank + patent rights as collateral + tangible assets as collateral)

- Other Financing Models

Investor loan combination: When the business is applying for a loan with the bank, private equity investors may intercede, signing cooperation agreements with the bank and the company after investigating the patent used for collateral; if the loan is not returned, the investor can enforce its debtors’ rights, according to the terms of the particular agreement, by selling the patent and taking a percentage of the proceeds or cooperating with or taking shares in the company.

- Still in Development

A. Pulling in Insurance: The company buys patent financing insurance in the process of offering its patent rights as collateral for a loan. If the company is unable to make loan payments on time, the insurance company will make up a certain amount of the repayment, depending on the stipulations in the contract.

B. Using the Licensing Revenue of a Patent as Collateral: After an individual or a corporation has entered into a legal licensing agreement with another party, a bank loan can be secured using the licensing royalties expected to be received over a certain period as collateral. The company then pays back the loan and interest according to the terms of the contract.

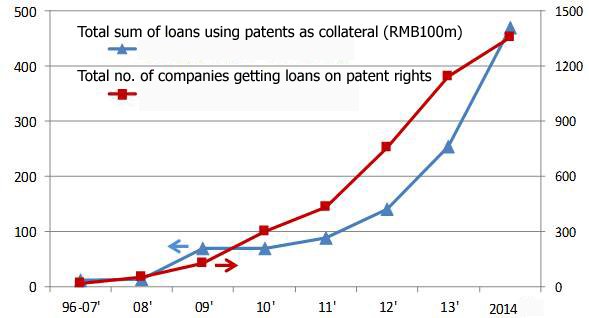

From 2008 to 2014 the total sum of loans secured on the back of patent rights has soared from RMB¥1.4 billion (US$201 million) to RMB¥56 billion (US$8 billion) along with the number of companies who have secured finance in this manner (See Figure 8).

Figure 8: Patent Financing Sum and Uptake, 1996-2014;

Source: Wang Shuanglong's presentation at the Cross-Strait Patent Conference

| |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

| Funds (RMB) |

1.4 bn |

7.1 bn |

7 bn |

9 bn |

14.1 bn |

25.4 bn |

48.9 bn |

56 bn |

Table 1: Funds raised by companies using their patent rights

Wang went on to state that the insurance industry has also expanded its reach to the patent arena, offering patent enforcement and infringement insurance, licensing insurance and assignment insurance. Patent enforcement insurance pays for investigative and legal costs to the patent holder during litigation to enforce their patent rights; whereas, conversely, infringement insurance pays court costs and infringement compensation in cases in which the purchaser unintentionally infringes another party’s patent.

There are currently nine cities in China which have launched patent insurance schemes, Nanjing, Jinan, Shenzhen, Chengdu, Zhenjiang, Jiaxing, Zhuzhou, Baoji and Foshan. There are also 44 experimental schemes in place, with 2779 companies paying a total of RMB¥15.2 million (US$2.2 million) covering 8,688 patents for up to RMB¥358 million (US$51.5 million). This is eventually expected to cover overseas infringement.

Summary of First Day

The first day of the conference focused on measures taken by both China’s State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) and the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office (TIPO) to improve patent quality and both delegations shared their policy-making experience on examination standards, promoting innovation and SEPs, including face-to-face consultations and seminars held for industry by government agencies.

TIPO launched a plan to help industry improve patent quality in 2014. Originally this was focused on trade associations, regional academic-industry cooperation centers and industrial development associations, but they later found that this approach had limited depth, and shifted in 2015 to focus on core companies with the potential to become industry leaders, as well as on boosting patent applications from national industries. This year, they added start-ups with a big demand for research and development, as well as the financial sector, to accommodate the government's FinTech policy. They have also attempted to address the fall in patent applications from universities. These promotional efforts are based around four main objectives, according to senior examiner and department head at TIPO, Hsieh Hsiao-kuang (see Figure 1):

Figure 9: TIPO's four objectives for improving patent quality and value;

Source: Hsieh Hsiao-kuang's presentation at the Cross-Strait Patent Conference

TIPO now offers customized consultation services to certain companies within five industrial sectors, biotech and pharmaceuticals, green energy, information and communications, precision mechanical instruments and cultural and creative design, selected for the number of patents previously filed in each field. These companies can request TIPO to assist in researching the current landscape of patents in a particular field or surrounding a particular technology.

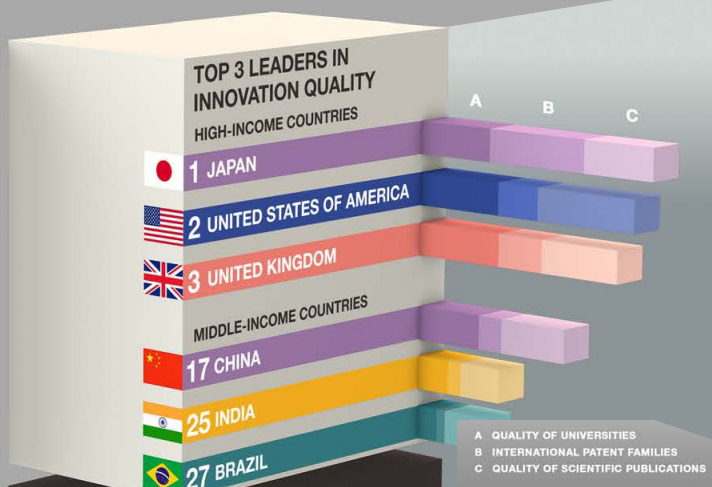

Despite China having more invention patent applications in total than the US and Japan put together in 2015 and becoming the first middle-income country to make the top 25 in innovation quality in the 2016 Global Innovation Index, the country ranked 17th overall, while Japan ranked first among high-income countries and overall (See Figure 2), with China's global patent families index in particular being well-behind that of high-income countries.

Figure 10: Leaders in innovation quality for high and middle-income countries;

Source: WIPO Global Innovation Index

While the country has dominated the top spot for invention patent application numbers for five years running, China’s intellectual property right trade deficit stood at RMB20.9 billion (US$3 billion) in 2015.

Addressing these problems, the head of the Application Quality Promotion Department of the Examination Management Division of the Patent Section at SIPO, Sun Dalong, stated that patent quality is rooted in three main things, technical quality, in terms of R&D and drafting technical features into a patent, legal quality, in terms of the quality of examination and being able to draft a patent which offers broad coverage and protection against infringement for the invention, and economic value, in terms of commercialization and market capital. He stated that each of these needs to be addressed to improve quality.

|

|

| Author: |

Conor Stuart |

| Current Post: |

Senior Editor, IP Observer |

| Education: |

MA Taiwanese Literature, National Taiwan University

BA Chinese and Spanish, Leeds University, UK |

| Experience: |

Translator/Editor, Want China Times

Editor, Erenlai Magazine |

|

|

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|