Figure 1: The promotional poster for Curse of the Golden Flower ; Source.

IP pledges, wherein forms of intellectual property such as patents, copyrighted content or trademarks are used as collateral for a loan, are an important component when structuring an IP monetization deal. Similar to mortgages on real estate that allow property owners access to finance without losing the title to their property, IP pledges allow the intellectual property right holder to monetize the inherent value of their intellectual property without having to sell it outright.

Deals involving IP pledges have been increasing in both volume and complexity over recent years in China. A snapshot of recent trends in the IP pledge market in China is provided below:

Copyright Pledges

- The accumulated balance of loans using copyright as collateral for 2015 was RMB¥2.9 billion (US$421 million).

- Copyright pledges are common in the movie industry. For example, as early as 2005, the movie Curse of the Gold Flower[1] secured a loan of US$10 million using its pre-sale contract as collateral.

Trademark Pledges

- The accumulated balance of loans using trademarks as collateral for 2015 was RMB¥51 billion (US$7.4 billion).

- Loans average at around RMB¥1 million (US$145,000). The largest recorded loan came in at RMB¥200 million (US$29 million).

Patent Pledges

- The accumulated balance of loans using patent rights as collateral for 2015 was RMB¥56 billion (US$ 8.1 billion).

- In the five successive years prior to 2014, the annual growth rate was around 100%.

Divergent Development between Different Kinds of IP Rights

Copyright and trademark pledges are now common practice. The facilitators of these deals are confident in pushing forward creative transaction models. Transaction volume has also grown steadily each year.

Patent pledges inspire less confidence, however, as, due to their legal characteristics, patent pledges involve more risk. These high risks have impeded the development of patent pledges in many countries, including China.

Patent pledges, wherein patent rights are used as collateral, are typically subject to the risks listed below:

Legal risks: The validity of the underlying patent is fundamental to the legal standing of the pledge, the reliability of the valuation and the monetary value of the patent when it is sold off to offset unpaid loans. However, the patent system was created in a way that a patent’s validity is subject to potential challenges throughout its lifetime.

Valuation risks: Valuing a patent is a complex task which requires a great deal of professional skill. Uncertainty can result depending on the approach by which the valuation is undertaken and the models and parameters used, all of which are very subjective.

Operational risks: The ultimate monetary value of a patent depends on the management skills of the person who utilizes the patent. This often cannot be foreseen during valuation.

Disposal risks: The process of selling off the pledged patent may be prolonged due to limited markets. A patent’s value often diminishes during this period of delay.

All of these risks are higher in China than in other countries. In China the valuation risk is particularly high given the absence of experienced professionals skilled in valuation and of a well-established credit system. Without any governmental interference, these high risks would have made the adoption of patent pledges in IP monetization deals impossible.

Incentives for Patent Pledges

The Chinese government has recognized these issues and has taken extraordinary measures to resolve the situation. Believing that “quantitative change will result in qualitative change”, the government has employed two tools to play the role of a market maker.

The first tool is interest rate subsidies. The government provides a risk premium to the bank extending the patent pledge loan. As one can imagine, the enthusiasm of the bank is proportional to the interest spread the government provides.

The second tool is a guarantee for the loan from the government. This is the stronger and more direct support of the two. The government participates in patent pledge deals through state-owned enterprises, which act as guarantors for the loans, using government coffers.

If a patent is valued at RMB¥10 million (US$1.5 million), for example, a bank may then grant a RMB¥6 million (US$870,000) loan to the patent owner with the government guaranteeing RMB¥5 million (US$725,000) of this. This means the bank faces its own risk to the tune of RMB¥1 million(US$145,000). The patent owner then pledges the patent to the guarantor, in this case the state-owned enterprise, as collateral.

Legal Frameworks for Patent Pledges

In line with the aforementioned administrative measures, legal frameworks are also being built up to support the rapid growth of patent pledges.

Two frameworks for patent pledges are currently available in China.

The first framework governs the pledge of a patent. This means the patent itself is the collateral. This framework involves relevant provisions in civil law, property law, patent law and various regulations relating to pledge transactions, centering around the Interim Administrative Regulation on Registration of Pledge Contract on Patent Right .[2]

The second framework governs the pledge of the patent’s derived rights (mainly royalties). The second framework is relatively new to the market, but it can be understood simply as a loan backed up by royalty payment flows over a certain future period when someone is utilizing the underlying patent. If a patent owner signs a licensing agreement with a manufacturer who utilizes the patent for production, the manufacturer agrees to pay annual royalties to the owner for the following 5 years, for example. The owner may pledge the rights to receive the royalty income (i.e. the patent’s derived rights) as collateral for a loan. As one can imagine, this kind of transaction allows for huge freedom in structuring patent monetization deals, helping to unlock the full value of the underlying patents.

The pledging of a patent’s derived rights has long been legally feasible under the Chinese legal regime, but not until 2015 has the government considered this type of pledge more seriously. In 2015, the competent authorities[3] jointly issued the Opinion on the Further Strengthening of Intellectual Property Use and Protection of Boosting Innovation and Entrepreneurship,[4] in response to the increasing attention being paid to IP monetization

Achievements and criticism

With these measures and legal grounds, patent pledges present opportunities for IP monetization not available for trademarks or copyright.

The practice has gained momentum. The incentive program started in 2008 and since then, the accumulated balance of this kind of loan has grown at a rate of 100% annually up to 2014 and may likely continue with a strong trend in the coming years, with many expecting it to soar to RMB¥100 billion (US$14.5 billion) by 2020.

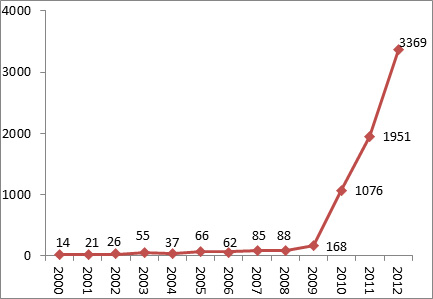

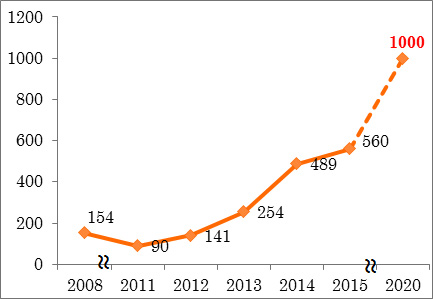

The chair of a leading technology company in China said, “IP financing is a novel idea but it is growing marvelously. The trend cannot be ignored by any runner of a high-tech company.”[5] Indeed, as shown in Figure 1 and 2 below, the growth in the number of IP pledge transactions and in the loan balance appear quite dramatic.

Figure 1: Number of Patent Pledge Transactions (from the book “Monetizing IP in China”, page 48)

Figure 2: Accumulated Amount of Patent Pledge Loans in units of RMB¥100 million

(from the book “Monetizing IP in China”, page 48)

However, there is still a lot of room for improvement and the practice has also been the subject of some criticism. Some have criticized the use of a strong scheme of incentives, suggesting that it is distorting the normal market function of resource allocation. Others are concerned that it will increase rent-seeking activities. Others still complain that, despite the strong governmental support, innovative small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) thirsty for funding are still largely excluded from such a policy. All things being equal, banks are still more inclined to deal with well-established companies with abundant physical assets to back up the loan.

A closer look at Figure 2 suggests a stalling point in 2015. The soaring growth trend from 2011 to 2014 appears to stop in 2015, although strong growth continued. This could be a sign that the incentive scheme has driven growth for years, but without the expected “qualitative change” at the grass-roots level, a bottle neck may have been reached.

How to Make the Most of this Opportunity?

In any event, the incentive scheme is likely to continue for at least five more years. From a practical perspective, one should focus on how to maximize the benefits now, while ignoring wrinkles to be ironed out down the road. In this regard, the three tips below may be helpful to facilitators of patent monetization deals.

- Enhance your eligibility. First of all, one must recognize that such incentives may not be readily available to everyone. Because state resources are involved, naturally it is easier for an entity that enjoys the government’s endorsement to obtain such support. Such entities are not limited to state-owned enterprises or domestic companies, however. Foreign-invested enterprises in China are also eligible if they are able to convince the local government that it is worthy of their support.

It’s preferable that the applicant makes the case themselves and this normally needs to include certain key ingredients: interesting technology, rock star founders, an original company and so on. It is essentially a game of image management. The applicant will need to tell a compelling story to help build credibility in front of the sponsoring stakeholders.

With the right story to tell, the stakeholders will be willing to make an endorsement, because they too have KPIs to fulfill and are seeking win-win opportunities.

- Establish a track record. Secondly, once the applicant has received a loan during the first round of fundraising, the second round will be much easier. The first instance of dealing with a bank in China is as difficult as in any other place in the world. It is how bank risk-management systems works globally. As such, one tip is to use a patent or several patents as leverage (see the third tip below) to obtain a smaller amount for the first loan, and then seek to expand the size of follow-up loans once you’ve established a track record.

- Leveraging but not reliance. The third tip is to form a collateral package including assets beyond patents. The bank will understandably be more willing to accept collateral such as a factory and manufacturing equipment, together with patents used in the manufacturing process than just the patents alone.

Consider the following scenario: assuming a bank is willing to grant a RMB¥10 million (US$1.5 million) loan by taking a factory and manufacturing equipment as collateral, what additional amount will the bank consider if patents are also added into the collateral package?

In seeking the answer, it is key to remember that the value of a patent is very subjective. In an arm’s length transaction, consensus on the valuation may be at least equal in importance to the opinions of independent valuers. It is also critical to remember that patent pledge loans are now encouraged under government policy. This means that for this particular category of loan the government is absorbing certain expenses or risks in favor of the related parties in the transaction. And of course, it is important not to forget that stakeholders have their own KPIs to fulfill under the planned economy – and they are also keen to see more successful deals.

Although there is no magic number, the inclusion of a patent or patents in a collateral package may change the nature of the collateral in the current environment. To a certain degree, such a change may be advantageous in obtaining a favorable interest rate or a larger loan. This is what I mean by leverage here.

About the Author

Dr. Jili Chung is a cross-cultural, interdisciplinary legal professional. He has worked in Washington D.C., Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, and Taipei for global law firms and multinationals, including as a senior lawyer at Clifford Chance and as executive director of Goldman Sachs.

He obtained his J.D. from UCLA, a Ph.D. in Law from Peking University, and an MBA and BS from National Taiwan University, and is qualified as an attorney-at-law in California and China, and a patent agent in China.

Dr. Chung is enthusiastic about exploring the values of ancient Chinese culture through IP mining and technological innovation. He is the author of IP Financing for Creative and High-Tech Industries (in Chinese by Peking University Press) and Monetizing IP in China (in English by Amazon).

More information on Monetizing IP in China can be reached via the Facebook Group or WeChat QR Code below:

- 《满城尽带黄金甲》(Man Cheng Jin Dai Huang Jin Jia)

- 《专利权质押合同管理暂行办法》

- The State Intellectual Property Office, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions, and the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League.

- 2015.9五部委《关于进一步加强知识产权运用和保护助力创新创业的意见》

- IP Financing for Creative and High-Tech Industries《文创与高新产业融资》

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|