Standard essential patent (SEP) infringement litigation has always played a part in the negotiation of the communications industry ecosystem, however, the communications sector in China has been rather late to the game, with Chinese communications companies only really starting to participate in international standard setting organizations (SSOs) after companies like Huawei and ZTE started to make moves on the global market. As Chinese companies started later, they've only really been able to take part in standard setting in the 4G and 5G fields, whereas they have had little input in terms of the 2G, 3G and Wi-Fi standards. However, as China has a large domestic market, the market there can function sufficiently well without setting foot overseas, which has led to the Chinese government often setting its own standards, and imposing these standards on companies that wish to enter the Chinese market. One example of this is the SEP battle over the WLAN Authentication and Privacy Infrastructure (WAPI), Chinese National Standard for Wireless LANS, which can be said to be China’s version of Wi-Fi. WAPI is a compulsory standard in China, which means that all phones which enter the Chinese market must have a WAPI function. The judgment on the first instance of a case filed with the Beijing Intellectual Property Court by IWNComm against Sony was made in March this year, and is expected to have a lasting impact on China’s patent litigation. IWNComm also filed suit against other phonemakers, including Apple and GOME at the Shanxi High People’s Court while their suit against Sony was underway.

Hong Yan at the conference in Taipei; Photos by Tommy Tang

At the recent conference in Taipei entitled ‘The Development of Patent Invalidity Proceedings and Patent Litigation in Mainland China and how Taiwanese Businesses Should Respond’, Hong Yan, a partner at Beijing-based law firm Lung Tin Intellectual Property, gave a speech on the IWMComm vs Sony case at the Beijing Intellectual Property Court in 2017. Hong gave four reasons as to why she selected this case, on which the first judgment was made in March of this year, as the topic of her talk: (1) Key players in the intellectual property field attended the hearing of the case, including Wan Gang, the head of China’s Ministry of Science and Technology, and Zhou Qiang, the president of China’s Supreme People’s Court. A first for a domestic patent verdict, suggesting the government’s increasing respect for patent battles. (2) It involved a standard essential patent, which has a wide impact on industry. (3) It represents a breakthrough in the court’s opinion (4) It is set to have a major impact on future litigation.

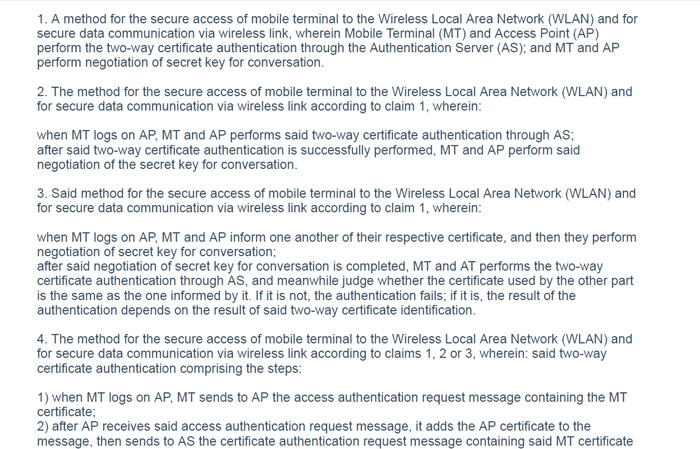

The plaintiff in this case is IWNComm, an active proponent of the WAPI standard and which holds many related patents. The claims of the contested patent, ZL02139508.X (‘A method for the access of the mobile terminal to the WLAN and for the data communication via the wireless link securely’), are identical to the WAPI standard identification statement.

Figure 1. The first page of the claims of the contested patent. The full claims can be found here.

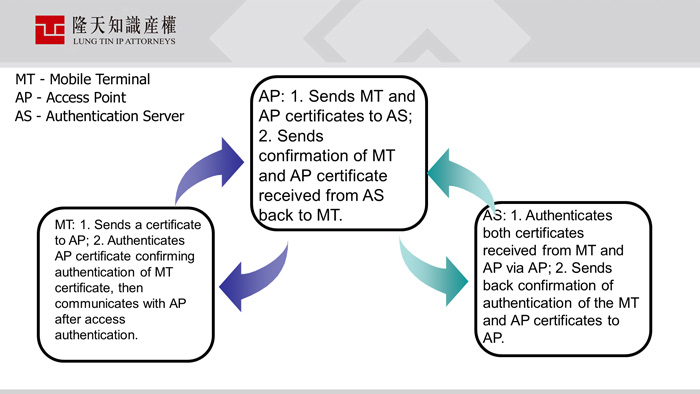

Figure 2: A diagram showing the steps delineated in the claims of the patent in dispute; Source: presentation by Hong Yan at the conference in Taipei (translated by Conor Stuart)

Figure 3 shows how the lawsuit rolled out, and, as Hong Yan pointed out, before IWNComm launched the suit against Sony, they'd already engaged in a long period of negotiation with the company, having demanded licensing fees from them from as early as 2009, but the two were unable to reach consensus. When negotiations broke down in 2015, IWNComm filed suit with the Beijing Intellectual Property Court in July of the same year. Sony then filed a jurisdictional objection, which was rejected both initially and then on appeal in November of 2015. Preparations for the hearing of the case then began. The case first went to court in February of 2016, and for the second time on December 21 of the same year. The first verdict on the case was reached quite quickly in March 2017. From the filing of the suit to the verdict on first instance this was a time frame of just 20 months. The decision was in IWNComm's favor, with Sony being confirmed as infringing, and being forced to halt infringing behavior and compensate IWNComm to the tune of over RMB9 million (US$1.3 million) in damages.

Figure 3: The progress of the lawsuit over time; Source: presentation by Hong Yan at the conference in Taipei (translated by Conor Stuart)

Hong Yan stated that there were three issues of contention between the two parties in the case:

- Did the defendant use the disputed patented method in the research and development, manufacture and testing of the allegedly infringing product?

- Can the allegedly infringing mobile terminal (MT) product manufactured and sold by the defendant implement the patent in question together with an access point (AP) and an authentication server (AS)?

- Does the defendants patent exhaustion defense stand up?

Point of Contention 1: Was there any testing after manufacture and does this constitute direct infringement?

To resolve this there were two points that needed investigation:

(1) Did Sony carry out tests of the WAPI function of the allegedly infringing product?

IWNComm provided a report authored by the China’s State Radio Monitoring Center Testing Center which proved that the L50t, XM50t, S55t and L39H model phones produced by Sony all had the WAPI function, although the WAPI chips were provided by Qualcomm. The court also requested that Sony provide information to enlighten the court on how Sony tests its products in the research and development phase (Hong Yan pointed out the similarity to the US discovery procedure here). Sony responded by providing the WAPI data they collected on four devices during the research and development phase; stating that tests had only been carried out on these four devices during research and development. Sony added that they had sent the phones to national authorities to be tested, and so it was the government body that tested the devices and so it was the government body that had implemented the patented method in question, not Sony itself.

(2) Did the tests that Sony carried out use the patented method?

Sony confirmed that 35 of its phones have the WAPI function (because this is unavoidable when selling phones in Mainland China), and acknowledged that the L50t, XM50t, S55t and L39H model phones had used the steps outlined in claims 1, 2, 5 and 6 of the patent in question.

The court decided: According to evidence provided by the plaintiff, the data on the tests during research and development provided by the defendant and the state ‘Quality Management System Demands’, all the handsets had to go through WAPI testing in the research and development, manufacture and post-production testing stages, a testing procedure identical to that outlined in claims 1, 2, 5 and 6 of the patent in question. On this basis, the court judged that the defendant had directly infringed the patent in using WAPI in the course of research and development, manufacture and post-production testing.

Point of Contention 2: Could the allegedly infringing mobile terminal (MT) product manufactured and sold by the defendant implement the patent in question together with an access point (AP) and an authentication server (AS)?

Hong Yan stated that this question involves multifaceted issues concerning the claim construction, with the implementation of the patent in question involving three steps:

Actions implemented by different modules/components/devices/;

Actions occurring in different locations;

Interaction occurring between different processes.

Hong Yan stated that in dealing with these kinds of claims, not all of the steps are followed by the mobile terminal user or the manufacturer, which means that laws and regulation surrounding enabling infringement or indirect infringement apply.

Article 21 of the Interpretation (II) of the Supreme People's Court on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Patent Infringement Dispute Cases, which took effect on April 1, 2016, reads, "Where a party, knowing that certain products are the materials, equipment, parts and components or intermediate items, etc. specifically for the exploitation of a patent, without consent of the patentee and for business purposes, provides such products to another party committing patent infringement, the people's court shall side with the right holder claiming that the party's provision of such products is an act of contributory infringement as prescribed by Article 9 of the Tort Liability Law."[1]

Hong Yan stated that according to the article cited above, the following elements constituting enabling infringement/indirect infringement can be interpreted:

Product specificity: the infringing product must be specifically designed to infringe

Knowledge of specific infringement, and knowing provision to others for business purposes: you need only be aware of specific infringement by the product

The exploitation of the patent rights by others: (i) infringing behavior has to have occurred; (ii) the language in the article mentions “committing patent infringement”, rather than just the potential to do so.

In regard to the above points, the view of both sides and that of the court are listed below:

(1) Specificity of infringing use

- The plaintiff argued that WAPI function modules, composed of the WAPI chip and WAPI modules, were equipment specifically used to exploit the patented method;

- The defendant argued that the handset product has substantial non-infringing uses and was not exclusively or specifically used to exploit the patent in question;

- The court was of the opinion that: after examining the equipment systems, the defendant's allegedly infringing product could connect to the WAPI network by installing WAPI related certificates. The defendant had also confirmed that 35 of its handsets had the WAPI function and that the hardware and software components and modules that make up the WAPI function have no other substantial use, other than exploitation of the patent in question.

(2) Knowing provision to others for business purposes

In terms of the issue of knowledge of infringement, the court was of the opinion that the defendant was aware that the defendant’s allegedly infringing product contains WAPI function modules, and that the combination of modules is for specific use in exploiting the patent in question. They did this without the plaintiff's permission, providing these products to others for business purposes.

(3)Infringing exploitation of the patent by others (cited directly from judgement)

The court was of the following opinion in this regard:

- Normally, indirect infringing behavior is contingent on the existence of direct infringing behavior.

- However, this does not mean that the patent holder needs to prove that another party has actually engaged in direct infringement, but rather they need only prove that default use of the defendant's infringing product "will" completely exploit the technological features covered by the patent rights. The issue of whether the user needs to bear responsibility for this infringing use is independent of the substantiation of indirect infringement: the reason behind this interpretation is that in some method patents, those who exploit the technical features in the patent claims in a complete way are mostly users, and because users, as they are doing this for "non-business purposes" cannot be considered to have infringed the patent. If one sticks to the logic of "indirect infringement being contingent on the existence of direct infringing behavior", that would lead to any patent method designed for use by users not being granted legal protection, which goes against the original intention of the patent law in allowing the grant of such method patents.

The last issue to be explored was whether use of a method patent involves

patent exhaustion?

The defendant argued that that the access point (AP) and authentication server (AS) equipment (IWN A2410) were the equipment that specifically exploited the patent rights in question, and as these were sold to the defendant in a legal transaction, this should mean that the patent rights have already been exhausted.

The plaintiff acknowledged that it sold the IWN A2410 equipment, but argued that this equipment was not specifically used to exploit the WAPI technology, and so the patent exhaustion should not apply in the matter at hand.

The court did not address the arguments raised by either party, only stating that patent exhaustion did not apply to method patents.

This opinion is based upon the first section of Article 69 of China’s patent law, which states, that after a patented product or a product directly obtained by using the patented method is sold by the patentee or sold by any unit or individual with the permission of the patentee, any other person who uses, offers to sell, sells or imports that product shall not be deemed to have infringed the patent rights”

In addition to this, Article 11 of the patent law states, “After the patent right is granted for an invention or a utility model, unless otherwise provided for in this Law, no unit or individual may exploit the patent without permission of the patentee, i.e., it or he may not, for production or business purposes, manufacture, use, offer to sell, sell, or import the patented products, use the patented method, or use, offer to sell, sell or import the products that are developed directly through the use of the patented method.”

Following the verdict, on April 20, 2017, the Beijing Higher People’s Court published a newly amended version of the Guidelines for Patent Infringement Determination 2017 (zhuanli qinquan panding zhinan 2017), which also contain an article relating to patent exhaustion of method patents. The fourth part of Article 131, under the title ‘Defense Based on Not Being Deemed as Infringement’, states:

“After the patentee of the patented process or its/his licensee sells the equipment specially used for exploiting the patented process, anyone [who] uses the equipment to exploit this process patent […] the act of using, offering to sell, selling or importing the product shall not be deemed as infringement of the patent right”[2]

This article suggests that this kind of behavior does constitute patent exhaustion and goes along with the opinions of both the plaintiff and the defendant, although it differs from the opinion of the judge on the case at first instance, according to Hong Yan, and this will likely be borne out when the case is heard on second instance.

Reexamination

Following the infringement lawsuit filed against them in the Shanxi High People’s Court, Apple unsuccessfully challenged the validity of the patent in a hearing of the Patent Reexamination Committee. Sony had previously unsuccessfully challenged the validity of the patent in similar proceedings.

IWNComm applied for a patent on the method in the United States in May, 2005. The patent application became the topic of negotiations at the Sino-US Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade for four years running from 2010-2013. The US patent was finally granted in October, 2013, and will be in effect for four more years.

- ‘INTERPRETATION OF THE SUPREME PEOPLE’S COURT ON SEVERAL ISSUES CONCERNING THE APPLICATION OF LAW IN THE TRIAL OF PATENT INFRINGEMENT CASES (II)’, CCPIT Patent and Trademark Office, http://www.ccpit-patent.com.cn/node/3219/3218 , Last viewed: May 22, 2017

- ‘Guidelines for Patent Infringement Determination 2017’, Yor Law, http://www.yorlaw.com/a/falvfagui/shangbiaofagui/20170427/299.html , Last viewed: May 23, 2017.

|

|

| Author: |

Conor Stuart |

| Current Post: |

Senior Editor, IP Observer |

| Education: |

MA Taiwanese Literature, National Taiwan University

BA Chinese and Spanish, Leeds University, UK |

| Experience: |

Translator/Editor, Want China Times

Editor, Erenlai Magazine |

|

|

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|