Figure 1: As Deng Xiaoping once stated, "It doesn't matter if a cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice."

The regulations of China’s IP regime are evolving rapidly. This presents challenges to IP-monetization professionals, who often find difficulty keeping abreast of the rapid changes. Furthermore, the current regime has many regulatory gaps. While these regulatory gaps allow a certain amount of room for innovation, IP monetization professionals often find themselves steering in uncharted waters.

In this context, what guidance is there for these professionals to assure them that they are on the right track? Or is there at least a framework for comprehending the constant changes, which can at first glance seem overwhelming and without an underlying logic?

The answer can perhaps be found by examining the guiding principles that policymakers adhere to in shaping the development of the contemporary IP regulatory regime in China.

Experimentalism

Chinese policymaking tends towards experimentalism. Thinking of things in this light, then, may provide an insight into the formation of regulation. This is especially true in a fast-paced sector like IP monetization which involves the financial markets.

Experimentalism in policy has strong precedents in China. The oft-cited quote from Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader who pushed market-economy reforms throughout the 80s, “crossing the river by groping for stones”, has permeated the development of various fields in the development of modern China. Innovation in the financial and IP sectors is no exception.

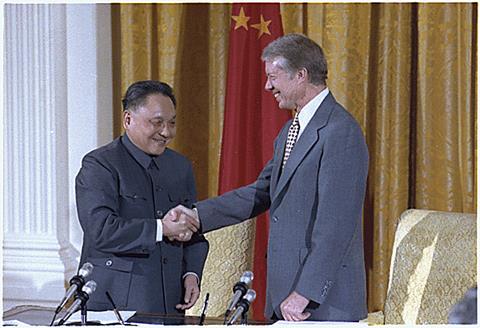

Figure 2: Deng Xiaoping and Jimmy Carter Shaking Hands by White House Photographer, 1979 (NARA)

The words of Deng’s speech from his 1992 South China Tour can be used to sum up the development of the Chinese financial markets over recent decades:

“Are securities and the stock market good or bad? Do they entail any dangers? Are they peculiar to capitalism? Can socialism make use of them? We allow people to reserve their judgement, but we must try these things out. If, after one or two years of experimentation, they prove feasible, we can expand them. Otherwise, we can put a stop to them and be done with it. We can stop them all at once or gradually, totally or partially.”

The statement reconciled the apparently inconsistent approaches of different market regimes and anchored financial innovation in the socialist market economy.

It’s interesting that, although this part of Deng’s speech has been widely circulated on the Internet, it does not appear in official records. The censorship or decision to exclude this quote points to the limits of the ideas contained in it. Deng’s words may provide some insight into the way policymakers think, but should not lull us into the assumption that the government will always embrace this kind of stance in regard to financial innovation.

Deng’s Impact

The ideas behind the words in Deng Xiaoping’s speech have been adopted by a variety of opinion leaders. In 2015, for example, 30 years after Deng’s speech, Dr. Wu Zhipan, an economic law scholar and vice president of Peking University, echoed Deng’s ideas in reference to financial innovation. He stated the following in his foreword to one of my books[1]:

“It is good to see all kinds of new financial products emerging in the market. The market economy has come a long way. We can be a little more daring now, however, with a supervisory system, credit system and a stable reserve of resources all in place. They are all far more mature than what was in place 30 years ago.”

This likely reflects the opinions of a significant proportion of intellectuals with regard to financial innovation and IP monetization.

The spirit of Deng’s words on experimentalism can be identified as the principle behind the IP monetization deals listed below:

Case 1: IP Co-Ownership through Securitization – First Steps

Using securitization to monetize IP is not new to China. This example took place more than a decade ago as part of a cultural exchange and involved the division of intellectual property rights into shares sold to different parties.[2]

In this case, the Tianjin Binhai New Area Tianjin Cultural Assets and Equity Exchange used a model involving co-ownership through the division of shares to monetize the underlying intellectual property rights of a specific piece of artwork. The work was a painting and so most of its IP value lay in the copyright arena. The exchange involved dividing the ownership of the artwork into shares, and selling them at auction. This resulted in the painting being sold for over RMB¥100 million (US$14.5 million) in total. This was one of the earliest experiments with IP securitization in China.

The case attracted media attention not just for its novel model, but also the record-high price of the deal. The artist was a college professor whose fame was limited to his own region. However beautiful the painting might be, its value had never been formally assessed by any acknowledged auction house, such as Sotheby’s. Without the securitization of the value of its intellectual property rights, the record-breaking price would likely not have been reached.

Case 2 - Monetization of Potential Intellectual Property Rights – 2008

In 2008, Chinese production company Huayi Brothers Media Corporation planned to shoot 14 TV series. To finance this project, Huayi worked out a creative financing model with a bank. Under this model, Huayi leveraged the scripts under development and their associated copyright as collateral for the loan. In this instance, this meant that the intellectual property rights that were used as collateral for the loan did not exist at the time of lending. In other words, the intellectual property rights were monetized before the creative content they protected was created. This was the first time a model like this had been used in IP monetization.

The success of this deal was considered a positive sign that the legal regime and markets respected the autonomy of both parties involved. It also suggests a degree of openness towards innovation in IP monetization in China.

Case 3 - IP monetization through Crowd Funding – 2015

Seven years after the experiment in innovation carried out by Huayi in the case study listed above, the 2015 blockbuster Monkey King - Hero is Back set a new milestone in terms of IP monetization in China.

The movie developer made good use of two IP monetization tools created in the Internet era, namely crowd-funding and social media.

It is easy to understand how crowd funding played a role in this IP monetization deal, as it worked in much same way it functions in other countries. It is more interesting to observe how social media contributed to the IP monetization deal, however, in terms of how it was financed, promoted and its relation to the regulatory framework[3].

Social media, combined with crowd funding, provided a platform for more than one hundred participants in this project. They would go on to share the securitized interest of the RMB¥300 million (US$43.6 million) box office, as well as future royalties from derivative products and other licensing activities of the underlying IP.

Pragmatism

In addition to the experimentalism showcased above, these cases also reveal a certain amount of pragmatism when it comes to innovation in IP monetization.

These creative IP monetization deals blur the boundaries of several traditional financing classifications from an academic point of view. However, academic theory is often secondary to the interests involved in practice. Regardless of its grey legal validity, the deals worked out for the parties involved. This shows the primacy of pragmatism when it comes to Chinese policymaking.

As with experimentalism, pragmatism, too, has its policy tradition in modern China, as indicated by another famous quote from Deng Xiaoping, “It doesn't matter if a cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice”, a metaphor he used to suggest that the politics of the economic model used was not as important as whether it helped to reach the goal of the development of the Chinese economy.

Experimentalism, along with pragmatism, enables the markets to try out novel models as long as they bring in profit without flagrant violation of the law.

Staying Within the Lines

Although the principles of experimentalism and pragmatism in policymaking may serve as a compass to help IP-monetization professionals keep innovative deals on track, or to at least provide them with a frame of reference in comprehending the ever-changing IP regulatory regime, this is not without its limitations.

The first line that should not be crossed is that of law and regulation. Given China’s recent touting of “Rule of Law”, laws and regulations are gradually gaining the respect they are accorded in most developed nations. The problem faced by many innovators in this field, however, is that there is no regulatory framework to comply with.

That leads us to the second line not to be crossed, namely, social stability. Although there is no regulatory framework to legitimize or illegitimize the methods used in the cases above and in other successful ventures, they have been manageable in terms of their greater implications for the broader society. In other words, the regulatory authorities are tolerant of innovative initiatives as long as social stability is not threatened as a result of any mishap. Social stability may still be the most important principle for policymakers; therefore it is important that IP monetization deals do not cross this line.

How to Proceed

The fact that China has a planned economy in itself suggests feasible courses for innovative IP monetization initiatives. The roadmaps under the planned economy regime often give account of how the government plan to allocate resources. In the IP sector, two national-level plans provide roadmaps for IP monetization.

The first is the Outline of the National Intellectual Property Strategy(Guojia zhishi caichanquan zhanlve gangyao) promulgated by the State Council in 2008[4].

Below are selected highlights from the outline relating to IP monetization. The government has committed itself to the following tasks over coming years:

- To encourage IP monetization

- To utilize financial or investment means to explore the value of IP.

- To encourage the origination of IP by the private sector.

- To utilize market systems to foster IP origination and utilization (i.e., including monetization).

- To expand international IP-related communication and cooperation.

The second roadmap is the Action Plan for Implementing the National Intellectual Property Strategy (2014—2020) (Shenru shishi guojia zhishi chanquan zhanlve xingdong jihua 2014-2020 nian).[5] It sets out clear milestones year by year in several IP categories.

The level of detail included in the milestones can be surprising, for example, the national average number of invention patents per 10 thousand people, has been respectively targeted at 4, 6, and 14 for 2013, 2015 and 2020. Once the targets are set, the governments at provincial or municipal levels plan corresponding milestones, and allocate resources accordingly.

An effective IP monetization plan must take these two documents as a roadmap for roll out.

This is a tremendous moment of opportunity for innovation in IP monetization in China, but the rapidly-evolving governance around IP in China and gaps in regulation may deter many enthusiastic professionals from getting involved. Awareness of the role of experimentalism and pragmatism in Chinese policymaking can offer a guiding hand. As long as no laws are broken and there is no threat posed to social stability, China welcomes innovative financial initiatives that foster IP monetization.

- IP Financing for Creative and High-Tech Industries (Wenchuang yu gaoxin chanye rongzi)

- Co-ownership through securitization is a status of legal ownership acknowledged by Chinese Civil Law. It means the co-owners may independently dispose of the interest represented by their respective shares in the property. A related concept is common ownership. Understandably, the former is more helpful in IP monetization, because it gives the individual owners the ability to dispose of their interest freely, and the potentially larger numbers of owners which facilitate the value-finding process of creative content and its associated intellectual property rights.

- A more detailed description of this case study can be found here: ‘How Social Media is fueling IP monetization in China’

- Outline of the National Intellectual Property Strategy, June 5, 2008 (English PDF: http://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/cn/cn021en.pdf )

- Download the English DOC file via the China IPR Blog here: https://goo.gl/ZNa12c

About the Author

Dr. Jili Chung is a cross-cultural, interdisciplinary legal professional. He has worked in Washington D.C., Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, and Taipei for global law firms and multinationals, including as a senior lawyer at Clifford Chance and as executive director of Goldman Sachs.

He obtained his J.D. from UCLA, a Ph.D. in Law from Peking University, and an MBA and BS from National Taiwan University, and is qualified as an attorney-at-law in California and China, and a patent agent in China.

Dr. Chung is enthusiastic about exploring the values of ancient Chinese culture through IP mining and technological innovation. He is the author of IP Financing for Creative and High-Tech Industries (in Chinese by Peking University Press) and Monetizing IP in China (in English by Amazon).

More information on Monetizing IP in China can be reached via the Facebook Group or WeChat QR Code below:

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|