Figure 1: Dr. Alexander Straus at a conference in Taipei, Nov. 23, 2016; Photo: Conor Stuart

If you are developing products that include a patented invention that you expect to enter several European markets in the future, then you may have become increasingly concerned over how Brexit will affect your options for patent rights and whether the plans for the unitary patent and the Unified Patent Court may be stalled as a result.

The Conservative UK prime minister Theresa May has stated that she plans to trigger Article 50 - which would set in motion the extendable two-year negotiation process for the UK’s exit from the European Union – before the end of March 2017. However, her power to trigger Article 50 has been challenged in a court case. May stated that she would trigger the article using royal prerogative, however, investment manager Gina Miller and another claimant won a challenge against this decision at the high court, which means that the government will have to seek parliamentary approval before triggering the article. The government has already appealed this judgment and is also working on preparing a bill on Article 50 which it will pass through parliament in the result it is defeated in the appeal at the Supreme Court. Scotland and Wales have been granted the right to participate in the Supreme Court appeal, which will start proceedings on Dec. 5.

Members of the UK parliament are unlikely to oppose the bill, however, even if the government is unsuccessful in the appeal, but does this mean that Brexit is still a certainty? At a talk in Taipei on Nov. 23, Dr. Alexander Straus, a German lawyer with Munich-based Becker Kurig Straus, cautiously predicted “an exit from Brexit”, whether before or after the triggering of Article 50. He cites the possibility of the opposition Labour Party running on a pro-EU platform in the event that an early election is called, the harsh line taken thus far on the Brexit deal by EU leaders and the estimated cost to the UK economy of the move, estimated at £59 billion (US$73.2 billion) over the next five years, as potential reasons for a U-turn. He stated that it remains unclear if the UK will still have to make payments to the EU after the Brexit to fulfill existing commitments, with some suggesting that such payments will have to continue until 2030.

Straus stated that the uncertainty around Brexit and economic challenges facing the UK mean that it is unlikely that the UK government will make a decision on whether it will ratify the plans for the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court in the near future. In any event, Germany is unlikely to ratify the agreement until after the German federal elections which will most probably take place in September 2017. The three nations with the most patents in effect in 2012 – Germany, France and the UK – are all required to ratify the agreement before it can enter into force.

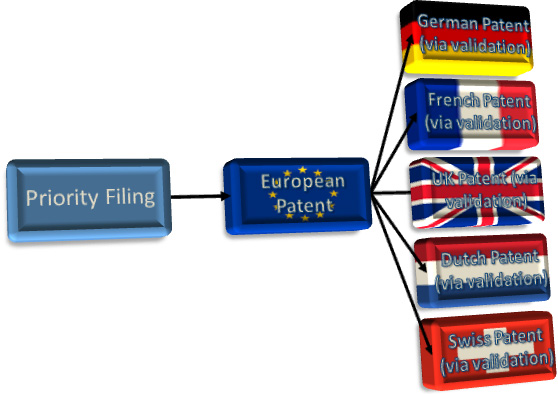

Figure 2: The various supranational organizations concerned with Europe; Source: The Emirr.

The current European system is governed by the European Patent Convention, which has 38 member states (some of which are EU members and some of which are not). This is primarily aimed at unifying patent examination in Europe, rather than creating a unitary patent. However, the Community Patent Convention in 1975 and the Agreement on Community Patents in 1989 were both attempts at this goal but were never entered into force. Other IP rights, such as trademarks, designs and plant varieties currently have EU-wide registration, but no such equivalent for patent rights is currently in force. The unitary patent is aimed at remedying this, with one single patent granted by the European Patent Office to be valid across all EU member states, except Spain and Poland (for the time being) and new EU member states, such as Croatia. Importantly it will not apply to the remaining 12 European Patent Convention states (see Figure 3).

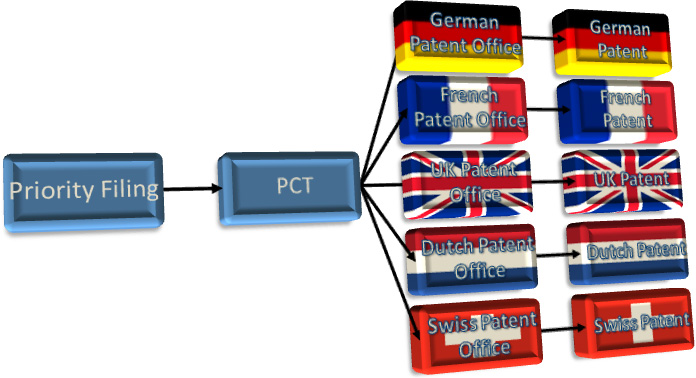

Under the current system there are several routes an applicant can follow to obtain patent protection in Europe, depending on whether the applicant is from a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) signatory country (Taiwan is not currently a signatory). Taiwan is a member of the World Trade Organization and a signatory of the TRIPS agreement, however, under which applications are recognized as having priority, except in China, where they are recognized under a cross-strait intellectual property agreement, but only for local applicants.

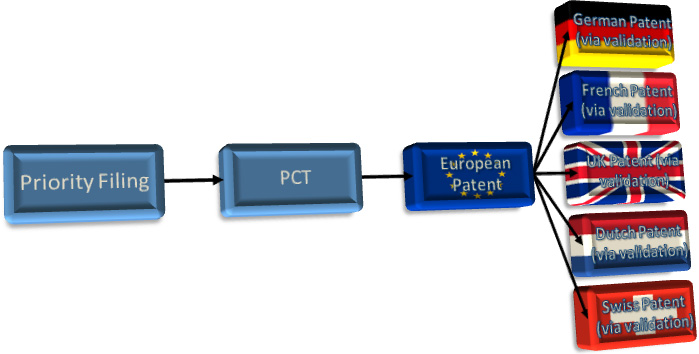

1. The European patent route

Figure 3: The European patent route

2. The Euro PCT route

Figure 4: The Euro-PCT route

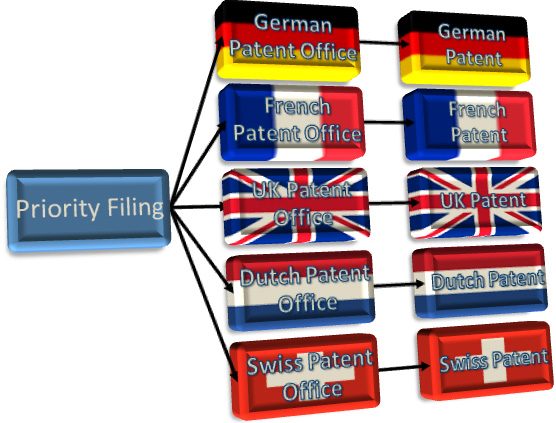

3. The national route

Figure 5: The national route

4. The national PCT route

Figure 6: The national PCT route

Whichever route one takes, the result is a bundle of national patents, rather than a unitary patent right for the European Union. This is expensive in terms of application or validation costs and when it comes to annuity fees, which must be paid for each patent in each country individually. Conversely, patent holders are allowed more flexibility in their maintaining or abandoning of their patent rights in different countries in the region.

It is the post-grant process that is most important for the unitary patent and, therefore, the likely grant date needs to be taken into consideration, rather than the application date, if a rights holder wants to be eligible for the unitary patent. If you wanted to apply for a unitary patent to protect your invention in 25 European Union member states, as well as getting protection for your invention in Spain, which has opted out of the unitary patent, and Switzerland, which is not in the EU, you would have to opt in to the unitary patent within one month of grant and submit necessary translations (only necessary for some countries during the transition period), as well as following the traditional EPC patent application procedure for Spain, and Switzerland (Figure 3-6). Subsequent renewal fees would be paid to the EPO for the unitary patent and to the national patent office for non-participating EPC member countries.

Infringement and validity issues will be handled by a Unitary Patent Court, with local divisions in each country and central divisions planned for London, Paris and Munich. Italy is the likely alternative for the UK, in the event that the patent court goes ahead if and when Brexit comes to pass.

The annuities for the unitary patent are to be calculated by adding the cost of annuities of the top four countries in terms of patents granted in the EU. Courts at the local level will be staffed with three legal judges, with an option of a fourth technical judge, while the central divisions will have two legal judges with the option of an additional legal judge or a technical judge. Dr. Straus was of the opinion, however, that it is unlikely that any division will not take up the option of having a technical judge in order to facilitate their understanding of the technology involved. The court of appeal will be staffed with three legal judges and two technical judges.

Once a patent is invalidated in the unified patent court, it is invalidated for every member country of the Unified Patent Agreement, which is why there is an opt out option for the agreement during a seven-year transition period. Patent holders who opt out can litigate their patent in national courts during this period.

Update: On Nov. 28 (the date of publication) the UK announced its intention to proceed with the ratification of the Unified Patent Court Agreement.

(Article updated Nov. 29)

|

|

| Author: |

Conor Stuart |

| Current Post: |

Senior Editor, IP Observer |

| Education: |

MA Taiwanese Literature, National Taiwan University

BA Chinese and Spanish, Leeds University, UK |

| Experience: |

Translator/Editor, Want China Times

Editor, Erenlai Magazine |

|

|

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|