Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen’s visit to SEMICON was an important validation for one of Taiwan’s most important industries. In addition to attending the opening of September’s expo, Tsai also invited industry leaders, including SEMI President and CEO Denny McGuirk, Taiwan Semiconductor Industry Association chair Nicky Lu, Advanced Semiconductor Engineering Inc. COO Wu Tien-yu along with other industry heads for a private audience. As the 5G era gradually dawns, demands on memory will be greater and greater, so we sat in on the Memory Technology forum at SEMICON to get a hint at the future direction of the industry.

|

Mr. Rod Morgan (Moderator)

Current Post: President, Inotera Memories Inc.

Previous Posts: Vice President of Procurement, Micron Technology, Inc.

Co-Executive Officer, IM Flash Technologies, LLC. |

Rod Morgan: We’ve talked about market trends, how mobile is really driving everything, how the advancement in capability and the technology in China is beginning to emerge as more of a driving force in the memory industry, as well as the IC industry overall. There’s also a gap that exists in what we perceive as the demand coming from China domestically as well. And, finally, there’s the technical issue: what are the barriers we’re going to have to break through and what are the limitations that may be in traditional memory that drive us to some new or different type of structure or technology?

Audience member: The first question I’d like to address to Mike [Rayfield], since he’s got a front row seat to the memory export market in general. There are two parts to it, one is very simple, more on the market numbers in particular; the other is a broader question.

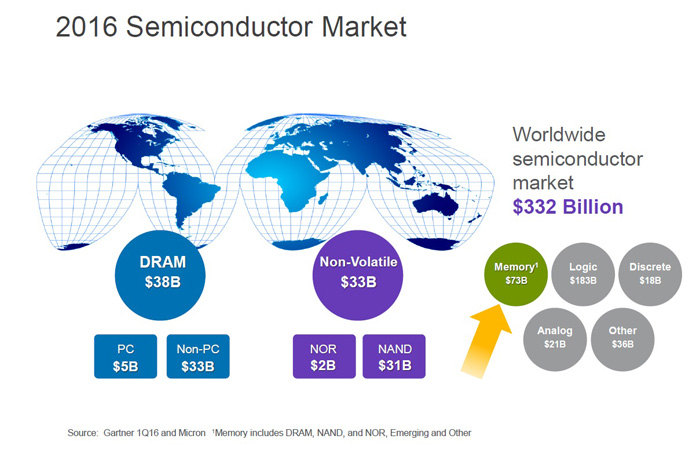

Figure 1: A slide on the value of the global memory market in the presentation of Mike Rayfield during SEMICON Taipei

The first one being, you showed a slide showing the memory market (See Figure 1), I remember it was a total of US$73 billion, but out of that you mentioned that only US$5 billion was in PC only. That number to me was a little bit… maybe that number didn’t include the server market? So maybe you could elaborate on that a little bit. And the second question is… I hope you’ve brought your crystal ball with you on your trip here. If you could share with us your vision for the coming years for the mobile market particularly. Samsung and Apple are the two big developers in the industry, making almost 100% of the mobile set profit. Do you see that continuing over the next few years, or do you see the other players gaining ground? Where we’ll see the industry get maybe a little bit more healthy. We all know a profitable industry makes everyone stay in the market and makes the industry healthier as a whole.

|

Mr. Michael Rayfield

Current Post: Vice President, Mobile Business Unit, Micron

Previous Posts: General Manager, NVIDIA

VP Sales and Business Development, Stretch Inc.

VP Sales and Operations, ReShape

Director of Business Development, Cisco Systems. |

Mike Rayfield: In answer to the first question, it was PC not including servers, so yes, you’re right. In terms of a crystal ball, the mobile market has got to be the only market that is the size it is: a couple of billion units a year. A market that I believe is still in its infancy. People talk about the mobile market, that it’s not growing anymore, that it’s over. But if you look through history, you go from mainframe, to minicomputer, to PC. Every one of those has built on the last one and the next one has been orders of magnitude larger than the previous one. So, mobile has just started. If you take your mobile phone apart and put an edge connector, you’ve got one of the most powerful servers in the world. If you squeeze it down and take away the display, you have the innards of a car, if you will. If you put it in your pocket, you have a mobile device. So, I believe it will continue to be a dominant factor in what computing architecture look like going forward. It will continue to put stress on how much memory and how much storage will be needed. I think in five years we’ll look back and go “Wow, 2 billion units a year really was just starting”, and that’s the fun thing about it. I think the innovation era is going to drive all kinds of other interesting mobile type markets.

Rod Morgan: Thanks, Mike. Maybe a follow-on to the question in relation to the comments on Apple and Samsung being the two only profitable areas, I wanted to direct the question to Michael Chen. Do you see the end market any differently, especially with the emergence of some fairly high volume companies in China going after that domestic market? Do you see an emergence in greater China?

|

Mr Michael Chen

Current Post: Executive Vice President, Chief Business Officer, XMC

Chairman of CASPA (Chinese American Semiconductor Professional Association);

Previous Posts: Executive in multiple listed companies in U.S.;

Various management positions in 4 start-up companies |

Michael Chen: Regarding the system hubs, China has lots of business based on the independent design house (IDH) model. Lots of small companies are generating local smart phones. In Wuxi, they have a high chip design capability regarding application processors, but also they bundle. They will sell you a phone. So they’re selling telecom equipment. Other than that, there are lots of others like Opal. Opal rose at the end of last year, and took over Xiaomi’s position. So it’s a very competitive market, regarding the cellular phone. Through the market competition, lots of the independent design houses and system part manufacturers, and also the vertically integrated companies, like Huawei, are generating [phones]. Based on my understanding, Huawei is the No. 1 in China, and second is ZTE. ZTE also bundles cell phones with equipment sales. They’re targeting developing countries like India. So, I would say, if you analyze Huawei, you’ll find it is earning money outside of China as a first step, this gives it the ability to come back into China. This is quite fascinating. I think that it’s possible that Huawei has surpassed many big companies, and even Apple already in terms of percentages, though not in terms of profit. Apple is still the No. 1 in this regard. I think this momentum will continue. So we need to look into what is profit and what is profiteering. The other aspect is market share. Market share matters. It also depends on when you are going to reap the harvest, to turn your market share into dollars. So I think there’s a lot of potential regarding Chinese domestic cell phone companies.

Rod Morgan: Thank you, Michael. Do you have anything to add to that, Mike?

Mike Rayfield: I think we’re still early in the game. So defining winning and losing is hard early in the game. And, to Michael’s point, in five years we’d like to be the person who owns the infrastructure, so you have control over, what we used to call CPE (customer-premises equipment) trade, which is your phone and your mobile device.

Rod Morgan: Before I turn it over to the room again. We talked about emerging technologies a great deal, and how companies can better focus their energy into developing and supporting the infrastructure around those emerging technologies. I’m curious as to what you see as the tipping point that is going to cause these emerging technologies to actually challenge the two fundamental faces that exist today with regard to non-volatile, with NAND and with DRAM.

|

Dr. Er-Xuan Ping

Current Post: Managing Director, Advanced Product and Technology Development, Applied Materials Inc.

Previous Posts: SanDisk, Micron |

Dr. Er Xuan Ping: In terms of NAND, if it were to be used as storage, I think that the current new memory wouldn’t be able to compete in terms of density. The development of DRAM is slowing down. So a lot of people are thinking about what will come after it. If DRAM technology is slowing down, then maybe the application of it has become saturated. Once the application of it becomes saturated because the technology is not progressing, then there could be a new application, as a storage class memory, so new memory can come in. So basically, because DRAM can’t evolve, there is a new need, which is an opportunity for new memory in place of DRAM.

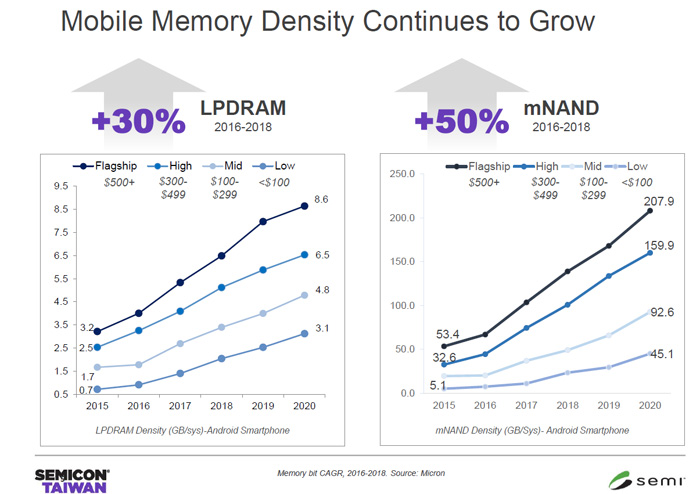

Figure 2: A slide on mobile memory density growth from the presentation of Mike Rayfield during SEMICON Taipei

Rod Morgan: I’d like to offer Dr Nicky Lu the chance to ask any question you have for the panel.

|

Dr. Nicky Lu

Current Post: Chairman, CEO & Founder, Etron Technology Inc.;

Chairman of Taiwan Semiconductor Association |

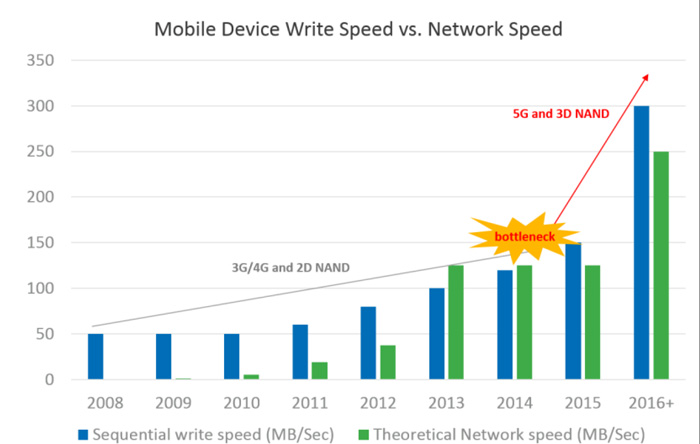

Dr Nicky Lu: This question is to Mike Rayfield. You showed NAND Flash jump and then you drew out the internet speed, the network speed right next to it (See Fig. 3). That’s very new to me. What does that mean? Because usually DRAM interfaces more with the network, or interfaces more with the CPU.

Figure 3: A slide on mobile device write speed vs network speed in the presentation of Mike Rayfield during SEMICON Taipei

Mike Rayfield: As you look at the richness of content, you think of 4K video, you think of very, very large frame buffer content which has textures and things like that, all of a sudden you have the ability to outrun your UM, just in terms of the sheer amount of content. And so you can imagine when you’re on a 5th generation network, when you have an 128 GB media file that you want to watch, you’ve got to find a way to get that in and out of your storage, not your memory. Now you may go in and out of memory to reduce jitter a little bit on the way in, but the reality is that the files are large enough and the content is rich enough, I’m going to have to be able to get the storage out of the way, and that means increased performance.

Dr Nicky Lu: What you mentioned has to do with memory structure. The second question is, for future heterogeneous integration, one of the key parts is memory. Today’s technology makes use of package-on-package (PoP) technology, but recently I noticed that TSMC has created integrated fan-out wafer level packaging (InFO-WLP) with redistribution layer (RDL) technology. Although the DRAM is still stacking up, the rest of the system on a chip (SoC) style chip can be made very thin. My question is what kind of evolution or revolution are you envisioning for progress on the DRAM part?

Mike Rayfield: The reality is for a given application, the first thing you have to ask is, “What’s the problem you’re solving?” There’s the problem of increased data, and we’re going about as fast as we can. We can’t go faster, so you have to start going longer. If you do that, then what you measure is how many pico-joules per bit to get something over to the SoC and all of a sudden you realize “Wow! It’s the interconnect, it’s the solder, it’s the package and things like that that cause significant consumption of energy.” So as an industry, we’re looking at different ways to get close to the SoC and burn less energy. And so I think you’ll see, depending on application and footprint, a bunch of those interesting things come up. The challenge is, because it’s driven by mobile, you have to be able to do it in the billions of units very rapidly. So you can’t have really esoteric technologies.

Dr Nicky Lu: I also have a question for Michael Chen. From your presentation it appears that you think that the big opportunity for China is to build up IDMs (integrated device manufacturers). If the projected $24 billion or even more, all go to build IDMs, I think it may be more profitable. And then China will absorb all our needs. Because let me tell you a joke. When people sell one NAND flash, and put it into a mobile device, the mark-up for that is eight-fold, akin to the mark-up for cocaine. If you go on to get an SSD (solid state disk), make this array, make an ECC (Error-correcting code memory), and some guys are selling this array for a real system, and it’s marked up 50-fold. Many semiconductor producers, including many of the people here are very sorry to hear this. A mark up of 50-fold is equivalent to the mark-up on opium. But, anyway, back to the question. Why does China put the money towards the component level, rather than on the IDM level?

Michael Chen: Based upon our analysis, most of the semiconductor companies, the product they are shipping, are based upon margin, which is a system format. The lowest one, regarding the shipping rate, is Micron, at only 53%. But with Samsung, for example, the figure reaches 83%. Probably the highest one is Intel. Packaging technology also matters. It’s a very highly integrated business model. All of these companies, they are not going to be shipping the modules, they are going to be shipping systems. For example, if you sell 28 modules, why don’t you combine them, bundle them and pool them with software and get 50% more of the gross profits? This is one of the reasons why EMC was acquired at the end of last year. There are all kinds of business models for different technology models, the question is how do you combine your technology model with your business model. This is very critical for success and for the health of the industry. The whole storage ecosystem is going to be reshuffled. This is a big plan and a great opportunity for all of you guys, including me.

Audience Member 2: This question is for Dr Ping. You mentioned that DRAM is slowing down. At what point will we see a migration?

Dr Er Xuan Ping: New fabs are expensive. The reason they are so expensive is due to all the patents. There are so many critical patent layers. This becomes very expensive. That means the shrink rate has slowed. Technically, one might be able to make a 50% smaller die, but if you look at the costs, it’s out of the question. This goes to the point that the money you add to shrink offsets any profit you might make. By now the shrink rate is less than 40-50%, maybe even less than 30%.

Audience Member 1: Can you share with us your view on the major price points for handsets over the next few years?

Mike Rayfield: There are still 2 billion people who don’t have a phone or an internet connection. They’ve never made a phone call and don’t have a computer. So, the thing that would have been hard to believe a couple of years ago is that those people would get all three of those things for under $100 that is probably as good capability wise as the iPhone 5 or the iPhone 6. That’s pretty incredible. So that makes a huge amount of growth. And then we’ve got to find a way to differentiate applications. And your phone is going to be your hub for your life, whether it be your car, the internet of things, and so it becomes ingrained with us that it’s something that you can’t do without. And as it gets that to the existing installed base, those 2 billion people, it’s a pretty big opportunity.

Dr Er Xuan Ping: The current benchmark, if you look at 3D X point from Intel and Micron, the cell size is very small, half-pitch is around 28-25 nanometer. So in terms of that cell working at high density, it’s already below 28 nanometers. Regarding STT RAM, we do have some evidence internally and maybe in the field that 28 nanometers is realizable for sure, and below that we are still experimenting. Our goal is to capture STT RAM for 10-7 nanometer, which means that the pitch of that STT RAM should be around 15 nanometers.

Audience Member 4: I think today it was interesting to hear about 3D X point, because it seems like it’s so disruptive of memory. It’s better than NAND, higher density than DRAM, so it seems like a game changer in terms of its impact on the NAND or DRAM industry. Also, in terms of the commercialization, when we think about ReRAM or MRAM, how long until it is commercialized? And how will Chinese makers respond to this new technology?

Mike Rayfield: So, 3D X Point is a good example of the issue we’re talking about. So the chance of any new memory overcoming the barrier that DRAM has in terms of reform is very low. The chance of any new memory overcoming the cost relative to NAND is very low. But 3D X point sort of sits in the middle where you have a relatively large storage and a very high performance relative to NAND. And so what I think you’ll start to do is you’ll see some of these really high-volume emerging memories show up as solving a little bit of the weakness of something like a NAND, which is broad performance, and solving a little bit of the weakness of DRAM, which is persistence and ultimately being able to get very large quantities of this memory with a very low standby. And so we’ll start to see lots of these little heterogeneous memories on the substrate to solve a problem and we think 3D X point is one of those.

Dr Er Xuan Ping: This goes back to storage class memory application. Storage class memory is itself new. So how the market starts applying this concept will take some time, with the establishment of standards and so on. That applies to 3D X point. With other new memory, MCU-wise, it will start in a year or two, but it will start very small. It will grow larger and larger with the development of smart cars and IoT, which will employ this new memory as a sort of benchmark.

[The above discussion has been edited for brevity and to render the speech of second-language English speakers more fluently]

|

|

| Author: |

Conor Stuart |

| Current Post: |

Senior Editor, IP Observer |

| Education: |

MA Taiwanese Literature, National Taiwan University

BA Chinese and Spanish, Leeds University, UK |

| Experience: |

Translator/Editor, Want China Times

Editor, Erenlai Magazine |

|

|

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|