Source: Miao Li’s presentation

“KEEP CALM, YOU’RE BEING WATCHED”, read the final slide of Miao Li’s presentation on how big data has disrupted the patent industry. This slide, taken from a meme generator riffing on the UK “KEEP CALM AND CARRY ON” motivational posters from the run up to the Second World War, has a likely unintended Orwellian feel in the post-Snowden revelations era. The intention behind it lacks the ironic or paranoid undertones often associated with the meme, however, and can be seen as an earnest call for calm in an industry that is changing from someone who has withstood scrutiny throughout her career. The meme is accurate in suggesting that the performance of everyone working in the patent industry is now being openly monitored and compared with others. The exhortation to remain calm is important too, in that although big data can inform examiners, litigators and judges of unconscious patterns in their behavior, it is not directly intended to render judgment on them, but rather it simply gives industry professionals a shortcut to the insights years of working experience might lend them. In the run up to the conference held by LexisNexis in Taipei, we sat down with Li, patent counsel and Asia training and onboarding manager for the company along with May Chung, responsible for the company’s sales in Taiwan.

|

Miao Li – Bio

Current Post: Asia Training and Onboarding Manager, LexisNexis

Prior Posts: IP Litigation Intern, Grünecker;

Patent Licensing Intern, Siemens;

Patent Counsel, Proctor & Gamble

Patent Counsel, ENN Group

Education: LL.M. in IP and Competition Law, Munich Intellectual Property Law Center |

| May Chung – Bio

Current Post: Sales Manager, LexisNexis Taiwan

Prior Posts: Manager, Corporate & Pharmaceuticals Management, Thomson Reuters (Taiwan)

Education: M.A. Library and Information Science, National Taiwan University |

|

IP Observer: Why did you set up a representative office in Taiwan?

May Chung: In and around 2011 LexisNexis set up an office in Taiwan, this was based on market size and potential, although the company had previously worked with a local agent to work on legal research solutions for academic clients.

Miao Li: I think that the local Taiwanese market has special characteristics, in that there are a lot of local businesses working in technological fields, like TSMC and HTC etc. They have a lot of innovative patents that have been filed in several other countries, as well as in Taiwan, so the quantity of patents applied for by Taiwanese companies is quite substantial.

May Chung: Yes. Taiwanese companies are often high up in the USPTO rankings of foreign applicants. […]

IP Observer: So your solutions are aimed at Taiwanese companies applying for patents in the US?

May Chung: Yes. Our solutions are aimed at Taiwanese companies applying for patents or priority in the US. Given that Taiwan is an island, the patent market here is very outward-looking. So when filing patents, many Taiwanese corporations focus on the US market.

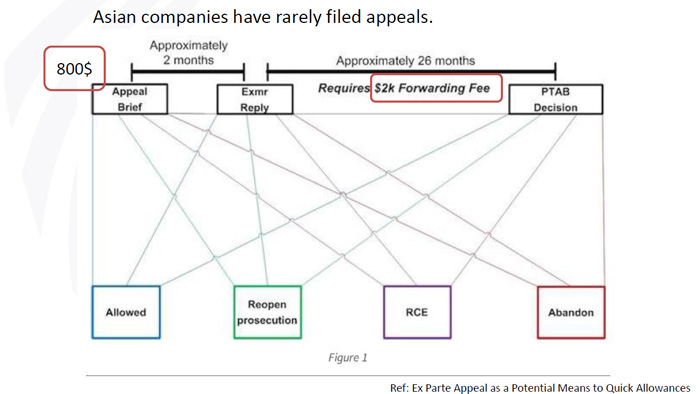

Figure 1: Statistics show that Asian companies rarely file for appeals, despite the fact that they can sometimes lead to allowances or a reopening of prosecution within 2 months; Source: Miao Li’s presentation.

Miao Li: Due to the size of the domestic market, Chinese companies set out to meet domestic demand first in terms of its research and development and then picks out a few of these developed technologies to patent abroad. It’s not that they have the US market in mind from the start [in contrast to Taiwan].

IP Observer: What impact is big data having on patent prosecution and litigation?

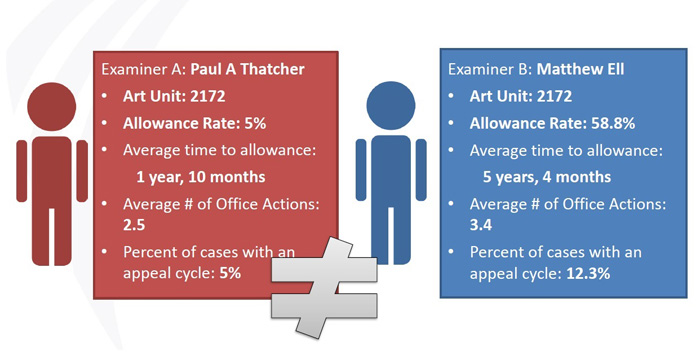

Miao Li: We have two specific products. One is aimed at people applying for patents in the US. This product has data on the approval rate and appeal approval rate of all of the patent examiners and technology centers at the USPTO. So when you see which examiner your patent is being examined by, you can look at their figures and assess if they’re more stubborn or easily persuaded, before deciding on your strategy. Do you insist on your claims? Do you decide on a telephone interview with them? Do you reduce your scope? And so on. Our intention is for our clients to use this kind of data to allow them to approach OA responses strategically, so that they can get the broadest possible claim for their patent in the shortest possible time.

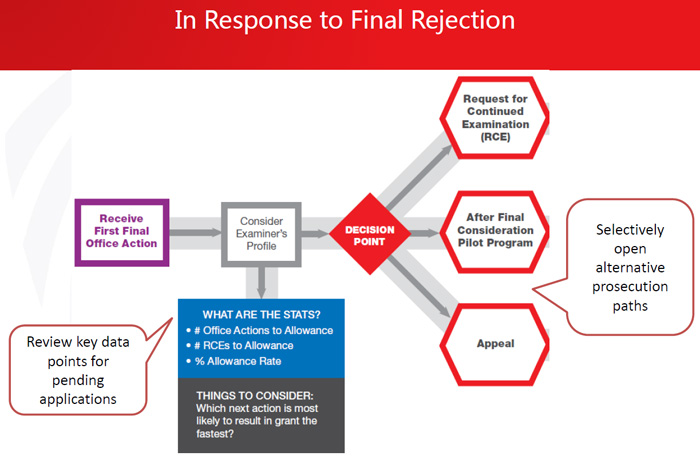

Figure 2: Data is useful in providing you with statistics to inform your decision; Source Miao Li’s presentation

This product is called PatentAdvisor, the result of a recent acquisition of the Minneapolis-based company PatentCore. The other product relates more to patent litigation. It’s similar to Patent Advisor in that it gives you data, but, in this case, the data is on US District Courts, their judges as well as different law firms, lawyers and companies. So you can make strategic decisions throughout the entire process of a lawsuit.

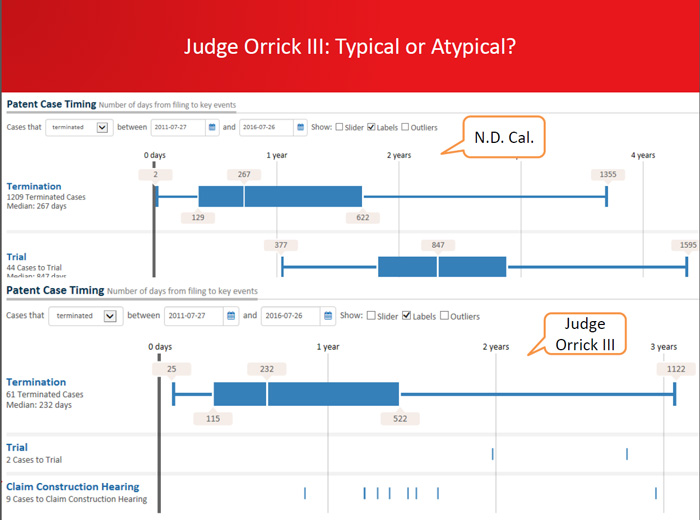

Figure 3: Graphics like this allow you to assess the speed of judges compared to the average for their district

For example, you might find that a certain judge has a fast pace at trial, or that another judge favors plaintiffs or defendants, or even that this lawyer has a particularly high success rate at bringing a certain kind of motion etc. And this information is accessible in an easy and quick way. This provides companies that aren’t based in the US with some real insights into US litigation. As far as I’m aware, although some Asian companies have experiences of litigation in the US, for the large part, they rely on advice from US law firms, so they largely just do what these firms tell them to do. This can make them feel like they’re not in control. Litigation in the US is unnecessarily complicated, but this tool presents information in a rapid and easy to understand way.

May Chung: As Miao just mentioned, there is often something simple that one can do, just one more step that can help you reach your aim of getting your patent granted or winning your litigation. Previously when you filed a patent, you would be powerless to do anything but wait until your patent was granted, or you got an Office action. You’re essentially left blind as to what will come next and how you will deal with it.

IP Observer: Do you think Taiwanese companies have enough understanding of the value of patents, particularly in regard to patent monetization?

May Chung: As one of the major drivers of Taiwan’s economy is the technology sector, companies here began to apply for patents relatively early on. In the very early days, people weren’t sure as to why they should apply for patents or as to what the larger goal was. In the early days there may have been internal demands made, like, for example, 100 new patents per year. These were very much quantitative goals, but this has gradually changed. However, it still depends on the company, not on the industry sector they are in or the scale of the company. It is contingent more on whether the leadership of the company understands the value of patent rights. Companies with that kind of leadership will engage in a different kind of work, particularly focused on the later parts of a patent’s life. They don’t just apply for patents for everything, but will have an internal strategy. Miao, for example, was at Proctor & Gamble before. Of course, they have an internal strategy. You have many ideas generated, and then these go to a technology committee and are sorted into around ten categories. Then the ideas are scored on their importance. So maybe lower value ideas won’t be patented or will only be filed in a limited number of countries, whereas high scoring ideas may be filed in 10 countries or more. This takes into account the renewal fees that will have to be paid down the line.

As to monetization, and whether or not they want to license the patent, that’s a different issue. Companies have to first do a valuation of the patent, and decide on the right course of action from there. But the leadership of companies in Taiwan often insists on owning the IP rights and assets and don’t like to cede them to others. Even if you tell them that they can earn licensing revenue, some business leaders will refuse from the outset. Perhaps their team understand what needs to be done, but the boss is not willing to do it. This may be for several reasons. One example I’ve heard relates to a company that had IP assets related to a business sector they were considering entering three years previously, but had decided against. So they could have licensed these IP assets. But in this case, the boss reportedly said “Are you certain that we won’t need to use these assets two years down the line?” He was not willing to accept the risks that come with licensing an IP asset, given that as soon as you license it out, you’re not able to use it in the event that you meet with other problems. Of course, some people address these risks through the agreement itself, writing it in a way that grants them the best possible deal. But people are less willing to license IP assets from you if you have an agreement that stipulates that you can use the technology too. It’s really a question of scope. So these business leaders aren’t willing to take on these risks, even though they’re aware of the value.

Miao Li: I think that a patent department in any given company does not start out with the idea of licensing or monetization in mind, as this comes a lot later in the patent lifecycle. Patents have a particularly long lifecycle, so many things don’t have any obvious value when we file them, but later we’ll discover that people in several fields want to use them. And there are other things which we consider very valuable on filing, but later they turn out to have little or no value. I think that it’s got to do with the timing of the valuation. It shouldn’t be done too early, but rather, you have to continually evaluate your patents throughout the entire patent life cycle. If you evaluate the patent too soon, then you’ll cut yourself off from many opportunities. The other aspect is that when you’re drafting a patent for a technology researched and developed by the company you represent, you have to consider when writing the specification if it will only cover the field your company is working in, or if it may cover a competitors’ field. You push to get broader claims so that it can cover more of the industry. You also have to consider if this can be developed into a family or portfolio of patents, which will be more valuable in terms of licensing down the line.

May Chung: It is when you’re at the licensing stage that people generally realize that the patent is not written well. As, every time that they [patent attorneys or engineers] draft patents, they’re just focused on the case at hand, they don’t think about the later developments. This is the problem they meet with after they’ve been granted the patent and are looking to license. So they may have a great quantity of patents, but they’re not good enough, so they can’t get a substantial amount of money for them.

Miao Li: We have another product which tackles this kind of issue – the PatentOptimizer. It’s a software tool which allows you to check the patent you’ve just drafted to see if there is sufficient support for your claims and for the terms you’ve used.

May Chung: As well as assuring your patent drafting quality, it also reduces your risk in the future as a litigant. This is because you can see how these terms have been used in US case law. Therefore if the usage and meaning of certain terms have already been defined in patent litigation, this can serve as a good indicator as to your risk in litigation. […] Terms are very important when something happens, and the use of one word versus another can have a substantial effect on the scope of your claims.

Miao Li: There is also PatentOptimizer for litigators. This is used when your aim is to invalidate a patent.

IP Observer: Do you see any emerging trends in the patent industry in China or Taiwan?

Miao Li: I think that the trends in China are very healthy and promising. In the past there were a lot of patent filings in China, an excessive amount even. However, among these there were a lot of junk patents, with many companies just applying for patents in order to earn government subsidies. The patents weren’t actually aimed at protecting the technology in question. This was a constant problem for the Chinese patent sector, so the Intellectual Property Office pushed patent examiners to be stricter in their examination to discourage these kinds of applicants. So in terms of trends, I would say that there might not be the sheer numbers of patents, but patent quality will rise. This will only continue with the recent establishment of China’s dedicated IP courts, allowing patent cases to be centralized there, where they had previously first gone to the People’s Intermediate Courts in different jurisdictions. Now they’ve been concentrated in these special courts with extremely capable judges whose focus is on IP. This will lead to a better standard and consistency in the judgments of patent cases.

IP Observer: How do changes in regulation affect this database? Does this lead to lag in how your software runs immediately after cases such as the Alice decision or the Myriad decision?

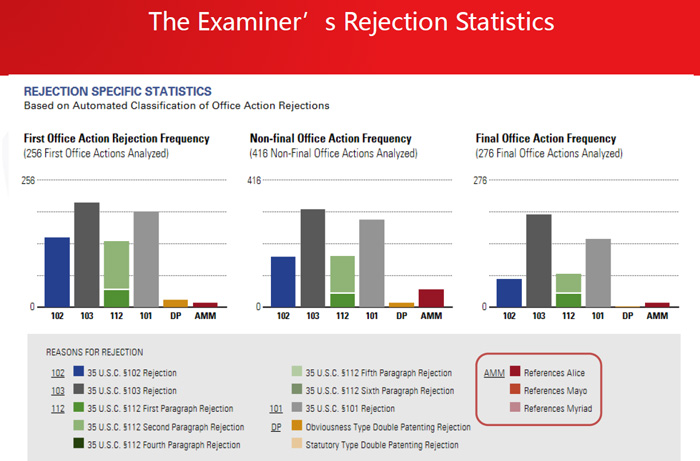

Miao Li: Actually our database is always updating and the changes in the regulation will also be borne out in the data. Like, for example, in the case of the Alice decision, which had a big impact on computer business methods, you could see that after the decision, there was a sudden drop in the patent approval rating of the technology centers which dealt with these kinds of patents shown on PatentAdvisor.

Figure 4: An examiner’s rejection statistics, including the number of times the Alice, Mayo and Myriad cases were cited; Source: Miao Li’s presentation.

These then got tagged as Alice rejections, and provide helpful information on the number of times a patent is rejected by a specific examiner citing the Alice decision. Conversely, you can look at those patents that were still able to get approval despite the Alice decision and look at how they drafted their patent and responded to Office actions. […] When your patent arrives at the USPTO, it will be directed by machine to a certain technology center depending on the specific terms used. Sometimes you might have a similar kind of technology, but the method you’ve written is different and your claims are different. In this case you may be directed to a different center. If you have two control methods for example, one is a control method for driving a car, it might be directed to the vehicles technology center, or it could be directed to a computing technology center. So the words you use are very important. If the method you write is different then you could be handed to a different technology center with a completely different approval rate. Some technology centers receive very few Alice cases. Really, we’re trying to help you to choose appropriate words in your claims to allow you a better chance of having your patent application handed over to the right technology center for you. This product is called LexisNexis PathWays. It provides word clouds for certain technology centers and displays the patent approval rates.

IP Observer: Have you thought about expanding into China in the future?

Miao Li: I think it’s not really a possibility, unless one day the head of the State Intellectual Property Office were to open access to Office actions. Currently you can see Office actions, but you can’t search them systemically. It’s only when you can do a systematic search that you can get the amount of information needed for the services we provide. This is also because it involves quite sensitive information. Just like in the US, when it comes to examiners, one might have a very low allowance rate, while another has a very high allowance rate (See Fig. 5), neither of which looks very good.

Figure 5: Source: Miao Li’s presentation at the LexisNexis Conference in Taipei

The USPTO has also begun to use our software to engage in performance reviews for examiners. In China, nobody would want information like this on one’s own work performance accessible by everyone. This kind of sentiment requires a lot of effort to overcome.

There’s been more progress in terms of litigation and certain companies have already been working on this kind of data repository for China. But although certain judgments have been published online, nobody knows if these are all the judgments. Without access to all the judgments, applying this kind of analysis is meaningless. The other factor is that only the final judgments are published online, data on the process, including motions, is not. Even though in the final judgment [the judge] will generally go through the entire process, it’s not like the US where all the information is readily available first-hand.

May Chung: At present we have a Lexis China legal database, but this isn’t specific to IP litigation, although IP cases are included. This means it doesn’t have the level of detail that we have for our products available for the US patent industry. The US is very open in terms of data transparency, as it puts it all online. But for other countries it often depends on the local government. The second region that we’re looking at is the European region, due to the data availability there. The first thing everyone tends to ask about is China, because of its market potential. […] This goes back to the motivation of Chris Holt when he started PatentCore [subsequently acquired by LexisNexis’s Reed Technology], in that he intended it as a force to improve the US system. It creates a virtuous cycle of improvement when your decisions and performance are subject to public scrutiny.

IP Observer: How does your product compare to solutions like that of former general counsel to Foxconn Jou Yanpeng’s WISPRO?

Miao Li: At the minute we don’t really do consulting. We really just offer clients the product itself. We just want our clients to get the best out of our products and to discover their own applications for the products. As an outside party, we don’t understand the company’s needs as well as they do, so they can get more out of the product by using it themselves.

May Chung: I think that there is a fundamental cultural difference here. We don’t provide consulting services in our IP business. We want our customers to make the final decision, after providing them with the data. Consultation reports in the West don’t generally provide you with a list of suggestions, but Taiwanese customers often demand of consultants that they tell them exactly what to do. This is not the accepted wisdom in the US or Europe, however. We’ve had a lot of clients who, despite being in the position of knowing their own business, their own clients and products better, demand that an outside consultant make decisions for them and give them some sort of guarantee on the outcome, that it will be profitable. But this is a risky kind of business to be in. We’re just in the business of providing you with statistics, and letting you make the decisions.

This article was updated on October 5, 2016, to more accurately represent the views of those interviewed, as well as to amend an incorrect date.

|

|

| Author: |

Conor Stuart |

| Current Post: |

Senior Editor, IP Observer |

| Education: |

MA Taiwanese Literature, National Taiwan University

BA Chinese and Spanish, Leeds University, UK |

| Experience: |

Translator/Editor, Want China Times

Editor, Erenlai Magazine |

|

|

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|