I have a question for the U.S. Supreme Court that also begs resolution “Where a patented design is applied to a component of a product only part of the time, should an award of infringer’s profits be limited to profits attributable only to the percentage of time that the design is applied?”

This fall the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments in the famous Samsung v. Apple infringement case involving US$399 million and a few narrow design patents. According to Samsung’s opening brief [1], specifically at issue is the question of “Where a patented design is applied only to a component of a product, should an award of infringer’s profits be limited to profits attributable to that component?”

Although the Justices and Learned Councils involved probably don’t need any of my help, I have another question for them that also begs resolution, should they have any free time. “Where a patented design is applied to a component of a product only part of the time, should an award of infringer’s profits be limited to profits attributable only to the percentage of time that the design is applied?”

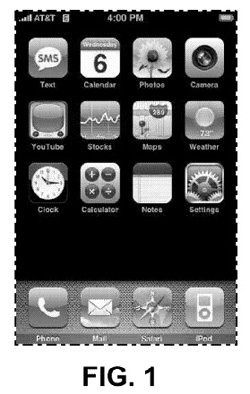

Figure 1: For your phone’s infringement of the 252,638 [3] utility patents used to give it form and function, Plaintiff is awarded US$120. For your phone’s infringement of the one design patent used only on the home screen, Plaintiff is awarded your “Total Profits”. / Public Domain

Compensation for infringement of design patents is addressed in 35 U.S.C. 289 [2], which reads (in part):

Whoever during the term of a patent for a design, without license of the owner, (1) applies the patented design, or any colorable imitation thereof, to any article of manufacture for the purpose of sale, or (2) sells or exposes for sale any article of manufacture to which such design or colorable imitation has been applied shall be liable to the owner to the extent of his total profit, but not less than $250, recoverable in any United States district court having jurisdiction of the parties.

What Samsung and Apple are concerned with in 35 U.S.C. 289 is what constitutes the “article of manufacture”. What I am talking about is the term “applied to the article” of manufacture when considering a patented virtual design, e.g. an icon, grid of icons, etc.

Figure 2: Apple’s patented icon grid D604,305 / Source

In their paper Virtual Designs [4], Jason Du Mont and Mark Janis do a nice “comprehensive analysis of design patent protection for design patents”. Of relevance here is their discussion of Ex parte Strijland in which “the Board recited the proposition a mere picture standing alone – surface ornamentation per se – could not be eligible subject matter” and “this deficiency could not be overcome by merely illustrating a picture on the screen of a computer unless it could be shown that the picture was actually an icon that was an integral part of the operation of a programmed computer” [5].

In 1996 the USPTO adapted the Strijland dicta as the governing approach for subject matter eligibility for virtual designs [6]. To satisfy the “applied to an article of manufacture” requirement, the USPTO says “Since a patentable design is inseparable from the object to which it is applied and cannot exist alone merely as a scheme of surface ornamentation, a computer-generated icon must be embodied in a computer screen, monitor, other display panel, or portion thereof, to satisfy 35 U.S.C. 171” [7], [8] (emphasis added).

While a patented virtual design “must be embodied in a computer screen”, in practice the virtual design may be visible on the screen sometimes and not visible on the screen at other times. For example, Apple’s patented icon grid [9] is visible on the home screen but may not be visible on some of the other system screens such as the settings page, during the use of an application, or when the device is locked or powered off, all of which constitute normal use.

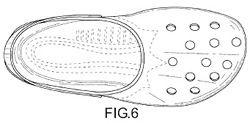

Douglas McAllister has published a good read on case law concerning design patents when at least a portion of the patented design is hidden from view during normal use of the article. Recited examples are items “such as colorful and representational vitamin tablets, or caskets [which] have designs clearly intended to be noticed during the process of sale and equally clearly hidden from view in the final use” [10]. Other famous examples where the patented design may be hidden in normal use are of a hip stem prosthesis [11] and of an insole of a Crocs shoe [12]. The paper’s conclusion is that recent trends suggest that a “hidden in use” test may only be used in determining ornamentally of a design, but that “the true test of ornamentally is whether the appearance of the article is a matter of concern either to the purchasing public or to the manufacturer” [10].

Figure 3: Vitamin Design Patent D430,662S / Source

So it seems like the answer to my question is probably “no” because virtual designs are applied to the computer screen and the fact that the virtual design may only be visible part of the time during normal use is not a problem as long as it is a “matter of concern” to someone. Yet, perhaps, it only seems this simple.

There is a major difference between virtual designs and those examples above that we haven’t yet considered. Take the case of the insole of the shoe as an illustration. There is no difference in the physical design of the insole regardless of whether seen because the shoe is not being worn or not seen because one’s foot happens to block the view. The patented design is still applied to an article of manufacture as required.

Figure 4: Crocs insole Design Patent D517,789S / Source

This is not true with a virtual design. According to the USPTO, the virtual design must be “embodied in a computer screen” to be eligible design patent material [7],[8]. However, as discussed above, an icon is not always displayed on the screen, for example when the icon that launches the settings page is replaced on the screen when the settings page is opened. Now the icon is no longer “embodied in a computer screen”.

In other words, unlike the insole design that is always applied to the shoe whether visible or not, the virtual design is only applied to a computer screen when displayed and is not applied to the computer screen when not displayed. The icon may be off lurking somewhere in memory waiting to be applied, but this is a tangible difference from actually being applied to the screen, especially when it is a generic screen explicitly designed to display an unlimited variety of images. At best, infringement can only occur when the icon is actually applied to the screen and does not occur when the icon does not appear on the screen to avoid running afoul of the statute.

Figure 5: Now you see it, now you don’t. / Public Domain

To be fair, 35 U.S.C. 289 does not say “permanently applied” and there may be those who would argue that because the virtual design, no matter how temporarily, is applied to the screen and is a “matter of concern” to some, that it falls within the letter of the law.

Regardless of whether this viewpoint is correct or not, any such interpretation of the statute to include “sometimes applied” seems to be a perversion of the spirit of a law originally styled as a design copyright proposal for specified articles of manufacture including “linen, cotton, calico, muslin, or other textile fabric, ornamentation on any article other than a textile fabric, and the shape or configuration of any article not falling into the previously mentioned categories” [13], which would all be permanent applications of the design.

Figure 6: Rug Design Patent D111,186S / Source

Moreover any such interpretation is not borne out by legislative intent. Referring again to the Samsung Brief, in the Congressional Record concerning the Patent Act Of 1887, “when Representative Hammond asked whether those profits arise from the use of the design alone or from various other circumstances which may enter into the manufacture, Representative Martin replied that ‘no such purpose was had in view by anyone who favored or urged the passage of the bill.’ And when Representative Hammond asked whether ‘the plaintiff may recover the entire profit upon the article of product, without any proof that this arises from the use of the design in question,’ Representative Martin responded, ‘I can not put any such construction on this law’” [14].

The fact that research revealed “consumers purchased Samsung and other Android phones overwhelmingly for their non-design features, such as screen size and quality, multimedia functions, and choice of wireless carriers” [15], even if true, is more or less moot here. What is relevant is that any reasonable person would concede that at least part of the value of a smartphone does rest in design, including virtual designs, and owners of those patented designs should be justly compensated. But you don’t get a speeding ticket every time you drive, only when you speed.

[Views expressed in in this article are exclusively those of the author and do not necessarily reflect views of NAIP or any of its affiliates.]

References

- Samsung-Opening-Brief-US-Supreme-Court, pp. (i)

- United States Code Title 35 – Patents, pp. 68

- The Smartphone Royalty Stack: Surveying Royalty Demands for the Components Within Modern Smartphones, Ann Armstrong, Joseph J. Mueller, and Timothy D. Syrett, pp. 7

- Virtual Designs, Jason J. Du Mont, Mark Janis, 17 STAN. TECH. L. REV. 107 (2013)

- Id. pp. 123-125

- Id. pp. 125

- Guidelines for Examination of Design Patent Applications For Computer-Generated Icons

- MPEP 1504.01, Statutory Subject Matter for Designs, 1504.01(a)(I)(A) Computer-Generated Icons

- Design Patent D604,305

- The Ornamentality Standard of Design Patents: Evolution and Rejection of The “Hidden in Use” Test, Douglas M. McAllister, Bridgeport Law Review, Vol. 13:419, pp. 419-452

- In re Webb, 916 F2d 1553 (Fed. Cir. 1990)

- International Seaway Trading Corp. v. Walgreens Corp., No. 09-1237 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 17, 2009)

- The Origins of American Design Patent Protection, Designing the American Design Patent System, Jason J. Du Mont, Mark D. Janis, Indiana Law Journal, Vol. 88:837, 2013, pp. 859-860

- Samsung-Opening-Brief-US-Supreme-Court, pp. 14-15

- Id. pp. 57

|

|

| Author: |

Daniel Gross |

| Current Post: |

Senior Engineer, Quality Control Manager, NAIP |

| Education: |

BS Computer Science and Engineering, University of Nebraska

Graduate work in the Human Computer Interface |

|

|

|

| Facebook |

|

Follow the IP Observer on our FB Page |

|

|

|

|

|

|